When consumers see the bright green “Sustainable” label on foods certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), many breathe a sigh of relief and drop the package into their shopping cart without a second thought. After all, what’s the point of a sustainability certification if you can’t trust the products it’s on to be produced sustainably? Most of us assume the certification has been vetted, the products inspected, any conflicts have been resolved, and the hard work has been done to ensure that the product we’re buying has been ethically produced.

If only that were the case.

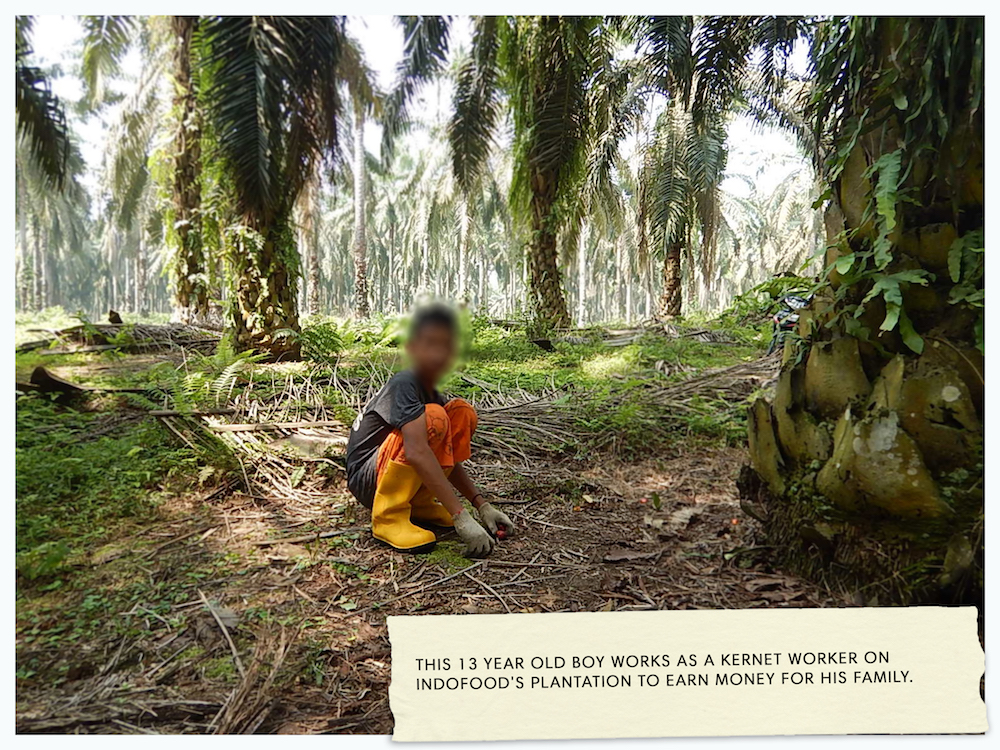

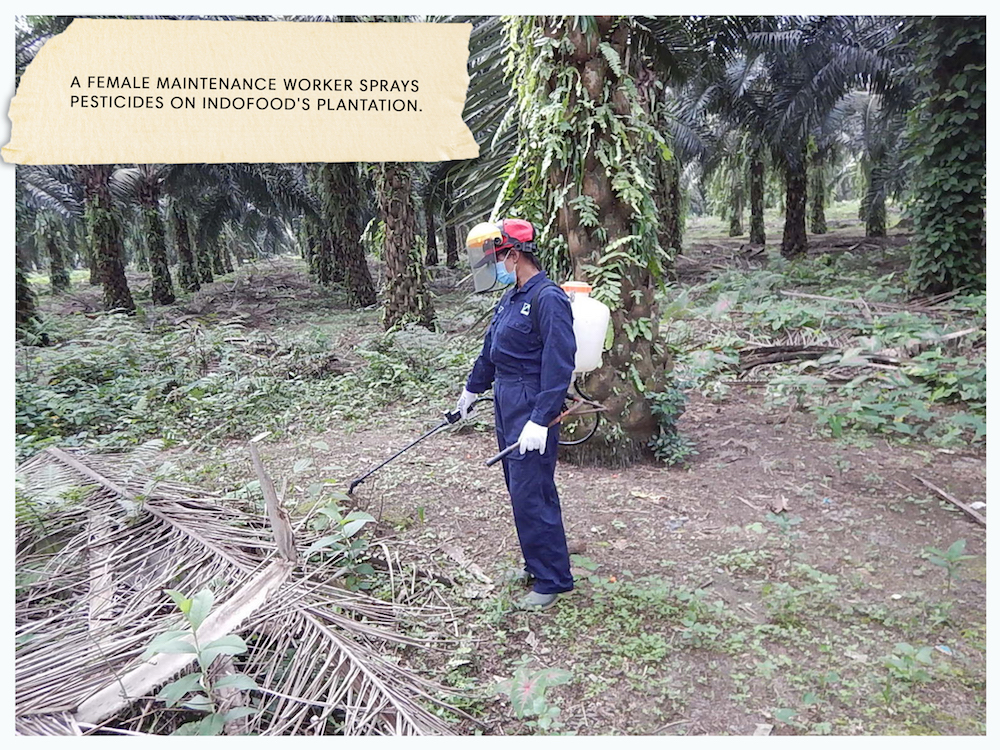

In June 2016 Rainforest Action Network (RAN), OPPUK, an Indonesian labor rights advocacy organization, and International Labor Rights Forum (ILRF) published a report investigating human and workers’ rights violations on the RSPO certified palm oil plantations of Indofood—Indonesia’s biggest food company, a major palm oil operator, and joint venture partner to PepsiCo, Nestle, and Wilmar. Through two months of intensive worker interviews on Indofood plantations, we found systemic human rights and labor violations, including child labor, workers exposed to highly hazardous pesticides, workers paid below the minimum wage, a long-term reliance on temporary workers to fill core jobs, and the use of company-backed unions to deter independent labor union activity.

Prior to publication, RAN and its allies provided Indofood with the opportunity to review and comment on the report’s findings, but the company simply denied all the claims, stonewalling behind threats to sue if the report was made public.

We, of course, published the report as planned, and six months ago today, RAN, OPPUK, and ILRF took our case to the RSPO, filing an official complaint against Indofood and calling for its suspension due the systemic violation of the RSPO’s labor standards. Half a year later, we still have no decision from the RSPO and in fact, we don’t even know when or if a decision will come. Meanwhile, workers on Indofood plantations continue to suffer violations of their basic rights.

The RSPO has not ignored our case. To the contrary, there has been a lot of activity on it, especially compared to other complaints in the RSPO system, many of which have been unresolved for years. Following the release of our report, the RSPO’s accreditation body Accreditation Services International (ASI) did an independent investigation on a third Indofood plantation, and they found a number of similar violations, including violations of Indonesian labor law, unsafe use and storage of pesticides, a lack of contracts for casual workers prior to 2016, contract terms for casual workers which prevent them from meeting the basic minimum wage, lack of registration for social benefits for all workers, and discriminatory employment terms.

ASI didn’t find child labor or informal workers (often called kernet workers) because the audit was announced to the company weeks in advance, giving Indofood ample time to clean up the most egregious labor violations before the auditors arrived. But ASI found enough violations of the RSPO standard that it suspended Indofood’s certification body in December 2016. Somehow, despite the suspension of the certification body, this was still not enough evidence for the RSPO to suspend Indofood as a member.

So here we are, six months later, with no decision and no timeline for a decision, and the RSPO continues to give its stamp of “Sustainability” to Indofood. Despite that big green “Sustainable” logo, Indofood workers continue to be paid below minimum wage. Workers’ quotas are still so high and physically demanding that often informal workers, sometimes family members, are needed to help meet them. And despite doing dangerous work and being exposed to toxic chemicals, workers continue to work without adequate healthcare.

The RSPO is at a crossroads: either it can choose to hold its member companies accountable to the standards it has outlined, or it can continue to whitewash members’ operations by allowing violations to go on unabated with no consequence.

In the words of an Indofood worker, “As for our work…we’re sanctioned if we do something wrong, cut fruit that’s not ripe. We get a deduction every time we make a mistake. When we make a mistake in our jobs, we get three warnings and then we get dismissed. We want that same level of accountability enforced for the companies and for the RSPO.”