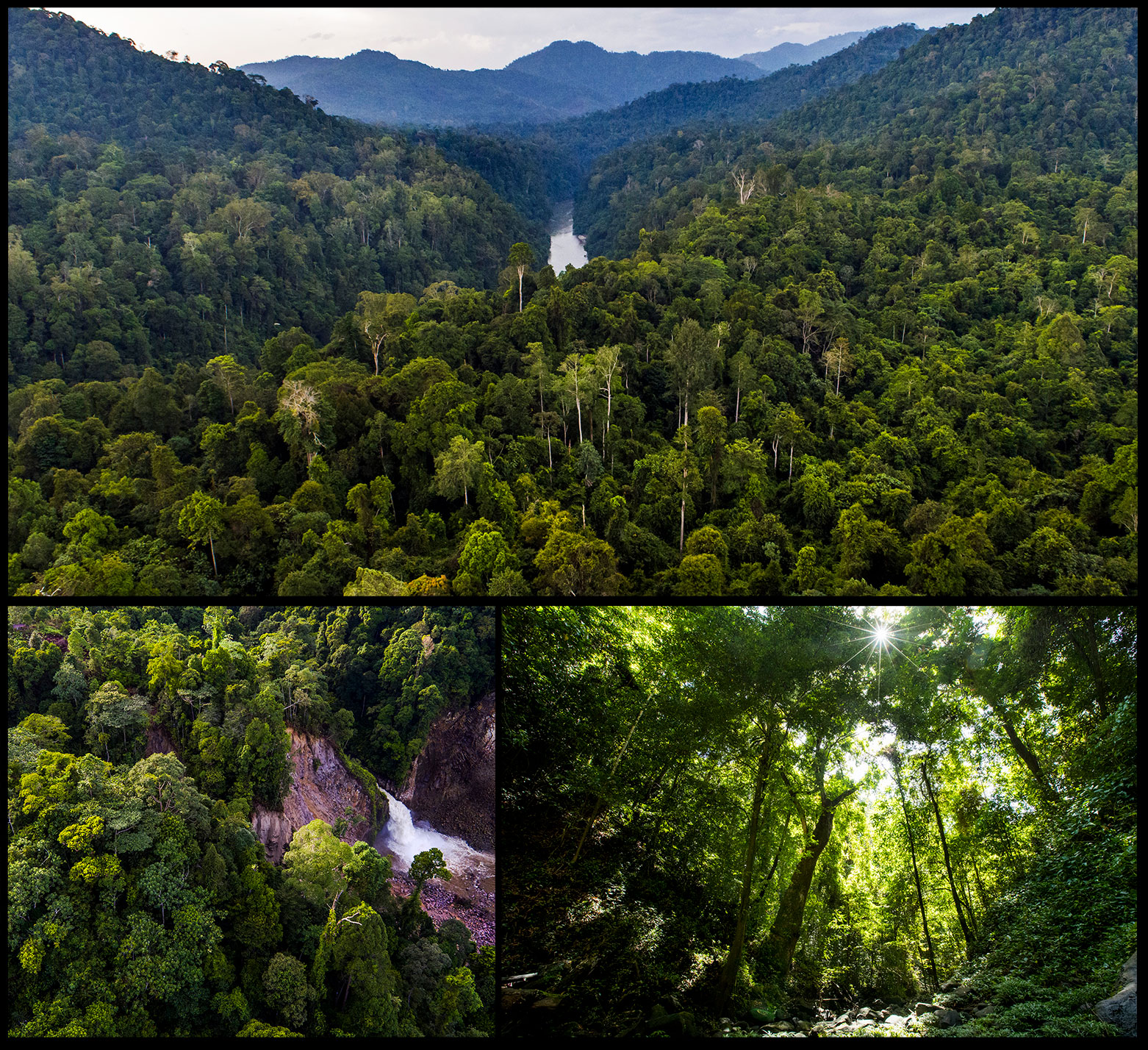

Can you picture a rhinoceros in the rainforest? Add a herd of elephants, families of orangutans swinging through the treetops and tigers prowling the understory and there is only one place in the world you could be. Indonesia’s Leuser Ecosystem is one of Earth’s most ancient forest ecosystems, a laboratory of life’s potential where the alchemy of evolution has been allowed to experiment, uninterrupted for millennia. And the results are astounding. Green upon green upon green, vines hanging from towering old-growth trees, moss growing on ferns growing on bromeliads growing on … you get the picture.

It is the kind of place one imagines primeval nature to be: wild, abundant, impenetrable.

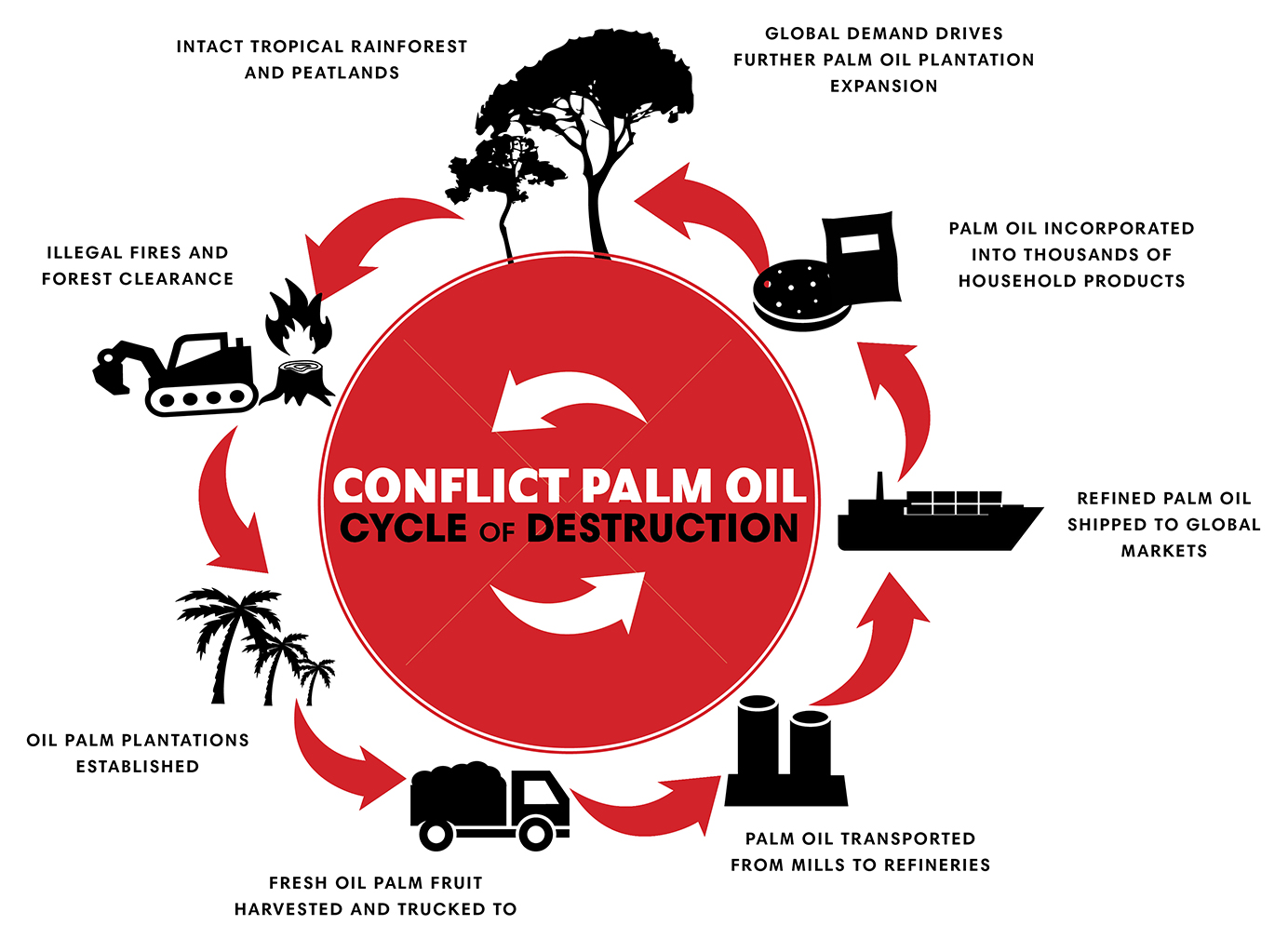

Tragically, undercover field investigations by my organization, Rainforest Action Network (RAN), have exposed major global food brands, including Unilever, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Mondelēz, General Mills, Kellogg’s, Mars and Hershey’s, sourcing illegal palm oil grown within the nationally protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

With more than a century of proud conservation history responsible for its continued existence, the province of Aceh where the Leuser resides, is, against all odds, a sparkling jewel of expansive ecological awesomeness standing in stark contrast to the devastated landscape that surrounds it. Most of the rest of Sumatra — once known as Indonesia’s “Emerald Island” — and sadly much of the rest of lowland rainforests across Indonesia too, have been exploited and denuded by wave after wave of scorched earth, industrial, colonial extraction and modern day corrupt corporate greed. What has already been lost is incalculable, but here, in this special place, remains a rare opportunity to stop the cycle of destruction and protect a globally valuable treasure before it’s too late.

It has been said that the Leuser Ecosystem is the heart of southeast Asia’s rainforest region, which, alongside the Amazon and the Congo Basin, is one of only three tropical forest regions on Earth. If so, then the Leuser itself wears its heart on its sleeve, and that beating heart is the lowland forests and peat swamps of the Leuser’s Singkil-Bengkung region. This area is part of the last remaining healthy peat swamp ecosystem in Western Sumatra. This lush jungle contains some of the world’s richest levels of biological diversity.

It would be hard to argue that there is anywhere on the planet more deserving of protection than the lowland rainforests of the Singkil-Bengkung. Dubbed the “orangutan capital of the world,” it is home to the highest population densities of critically endangered orangutans anywhere. This includes a special, culturally distinct subpopulation of a few thousand individuals, which demonstrate social structures and tool-using behaviors unique from all other orangutan populations. These forests are also home to some of the healthiest remaining breeding populations of highly imperiled Sumatran elephants, rhinos and tigers.

The health of the Leuser Ecosystem’s Singkil-Bengkung landscape is internationally significant because its deep, carbon-rich peatlands are among the most valuable and effective natural carbon sinks on Earth. Conversely, when drained, cleared and burned for conversion to palm oil plantations, this soil type is transformed into a carbon bomb that emits catastrophic levels of pollution into the atmosphere.

Hundreds of thousands of people rely on the area’s rich natural resources as the basis of their livelihoods. Downstream villages are already suffering severe, sometimes deadly threats from devastating floods, landslides and the loss of subsistence resources like fish and forest products as a direct result of the rapid rates of deforestation caused by palm oil. Communities also continue to suffer due to the loss of access to their customary lands that have been taken over by palm oil companies, without their consent, and failures of the government to take decisive action to resolve conflicts and restore communities rights to their lands.

The Acehnese people have fought for over a century to protect the integrity of the Leuser Ecosystem’s extraordinary forests, and in the past decade the Leuser has become internationally famous for its intact expanses of verdant trees and its stunning wealth of charismatic and imperiled wildlife species. But also over the past decade, over 18,000 hectares of forests within Singkil-Bengkung region has been cleared, leaving roughly 250,000 hectares of rainforests remaining, although this area decreases each and every year due to deforestation and the drainage of peatlands.

RAN conducted the series of undercover investigations in 2019 due to the alarming destruction of peat forests occurring within the lowland rainforests of the Leuser Ecosystem. The field research was conducted to determine if the forest clearance was being driven by major snack food brands, even though these brands had adopted policies years ago to end deforestation in their supply chains. The results of the investigations are definitive. Palm oil is being grown illegally inside the nationally protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve and that oil is being used to manufacture snack foods sold across the world by Unilever, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Mondelēz, General Mills, Kellogg’s, Mars and Hershey’s.

The brands named here have been found purchasing palm oil from mills that have continued to source palm oil resulting from the illegal clearing of lowland rainforests within the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. These mills are located immediately next to areas of illegal encroachment into the Leuser Ecosystem and lack the necessary procedures to trace the location where the palm oil they sell is grown, a key requirement for complying with the No Deforestation, No Peatlands, No Exploitation (NDPE) policies to which all of these brands have publicly committed.

Progress has been made by some companies implementing their No Deforestation policies, brands like Unilever and Nestlé, for example, have begun the process of increasing supply chain transparency by publishing the mills they source from, but they have not yet achieved traceability to the plantation level so they remain unable to offer certainty as to exactly where the palm oil they consume was grown. The findings of these investigations clearly show that paper promises are not enough to keep the forests from falling.

The Leuser Ecosystem at large, and the Singkil-Bengkung region in particular, still offer a rare and fleeting opportunity to get it right and avoid the devastating mistakes made throughout so much of Indonesia in the past. It remains possible here to prevent the destruction of habitat that drives iconic wildlife species toward extinction, to avert the human suffering from inevitable floods and landslides caused by deforestation, and to end the reckless burning of carbon-filled peatlands contributing to the climate crisis.

The international attention resulting from the release of this latest report has helped to pressure the brands to respond and take further action, but the high stakes and urgent threats to the Singkil-Bengkung demand more bold, decisive action to ensure that the area receives permanent protection.