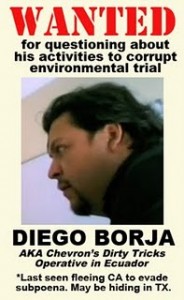

Perhaps you saw the news last week that Chevron’s self-described “dirty tricks guy” in Ecuador, Diego Borja, has fled California to evade being served with a subpoena. I feel compelled to say something here, because if this isn’t the height of hypocrisy and a shocking admission of guilt, I don’t know what is.

Perhaps you saw the news last week that Chevron’s self-described “dirty tricks guy” in Ecuador, Diego Borja, has fled California to evade being served with a subpoena. I feel compelled to say something here, because if this isn’t the height of hypocrisy and a shocking admission of guilt, I don’t know what is.

Borja, a Chevron contractor, was recorded talking about his efforts to corrupt the trial in Ecuador by entrapping and bribing the judge, tampering with evidence, and other dirty tricks. Now, Borja is on the run to avoid questioning, though two US Federal courts ruled that he should be compelled to testify.

By contrast, when Chevron’s lawyers sought to compel Crude director Joe Berlinger to turn over outtakes from the film, he fought back on the grounds that he needed to protect his journalistic sources — an argument supported by the International Documentary Association as well as documentarians like Michael Moore, D.A. Pennebaker, Louie Psihoyos, and Morgan Spurlock. But ultimately Berlinger complied when the court ordered that he turn his footage over.

Consider also the fact that lead US lawyer for the Ecuadorean plaintiffs Steven Donziger is currently facing not one but multiple depositions as Chevron’s lawyers are trying to compel him to divulge everything and anything they can, on a fishing expedition for information they hope they can use to portray the entire lawsuit as fraudulent. Donziger surely isn’t happy about Chevron wasting his time and grossly misrepresenting his actions, but he’s complying.

And why are Berlinger and Donziger complying? Because while they may not like it, they have nothing to hide.

On the other hand, when the tables were turned on Chevron and Borja was about to be served with a subpoena, what happened? Borja up and fled his posh California home in the shadow of Chevron’s headquarters. Why would he flee, unless it was imperative to him and the company that he not be compelled to divulge what he knows about his and Chevron’s attempts to corrupt the trial in Ecuador so that the company can evade its responsibility to clean up its toxic oil pollution in the Ecuadorean Amazon?

Of course, I have no evidence that Chevron helped Borja, his wife (who has also been implicated in evidence tampering), or his American partner in crime, Wayne Hansen, flee California. Nor can I prove that the company told them to flee before being subpoenaed. But we do know that Chevron was paying Borja’s $6,000-per-month rent for his fancy California digs, and we also know that Borja has claimed in the past that he has evidence so damning that it would prove Chevron’s guilt and win the case for the plaintiffs. I’m just connecting the dots here.

Chevron and its lawyers have spent a lot of time and energy lately trying to make allegations that it is in fact the Indigenous and campesino plaintiffs and the Ecuadorean courts who are guilty of fraud. But you have to ask yourself: Why is Chevron’s dirty tricks guy acting so guilty? What does Borja have to hide? And how likely is it that Chevron is trying to keep Borja and whatever he knows hidden? To my mind, Borja fleeing the subpoena shows who has the guilty conscience — and it ain’t the plaintiffs.

Imagine, for a moment, if Berlinger and Donziger had gone into hiding rather than face the music. What would Chevron’s lawyers be saying about that?

If Chevron really believed itself to be the innocent party in this whole affair, why wouldn’t the company force Borja to comply with the subpoena and set the record straight? The plaintiffs’ lawyers and related parties are complying with court orders to divulge what they know, because ultimately anything revealed may be embarrassing, but not damning.

The answer is simple, and obvious: Chevron is guilty as hell, Borja can prove it, and all of them are desperate to avoid being compelled to divulge that fact.