Updated: July 22nd, 2019

Banks and investors are under increasing scrutiny for their financing of the palm oil sector, and rightly so. The environmental, social, and governance (ESG) risks associated with this controversial sector — illegality, land grabbing, peatland and rainforest destruction, and labor abuses, to name a few — can carry significant reputational and financial risks for financiers. As major banks and a handful of investors tighten their standards on financing palm oil and other forest-risk commodities, it’s worth taking a look at how the financial sector is reacting to one publicly listed food and palm oil company, PT Indofood Sukses Makmur Tbk (“Indofood”) (INDF:IJ), which was recently ousted from the world’s largest palm oil certification body.

Indofood – a rogue company in disguise

A flagship company of the Salim Group, Indofood has a market cap of 4 billion USD and is Indonesia’s largest food company as well as the world’s largest instant noodles manufacturer. It also has the second largest oil palm land bank in Indonesia through its subsidiary Indofood Agri Resources. But the company is not without controversies.

In October 2016, Rainforest Action Network (RAN), International Labor Rights Forum (ILRF) and Indonesian labor rights organization OPPUK filed a complaint against Indofood’s palm oil subsidiaries for violating the certification standards under the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). Multiple investigations by RAN, OPPUK and ILRF, as well as the RSPO and its accreditation body, confirmed the presence of exploitative labor practices in Indofood’s palm oil operations — including cases of child labor, unpaid workers, precarious employment, gender discrimination, and toxic working conditions. In affirmation of these findings, the RSPO issued a decision in November 2018 that required Indofood to address worker exploitation in its subsidiary’s operations, including over 20 violations of the RSPO standard and 10 violations of Indonesian labor law. Indofood’s refusal to submit the required corrective action plan left the RSPO no choice but to terminate Indofood’s RSPO certificates and cancel its RSPO membership in March of this year, while leaving Indofood’s workers without remedy for the harms committed.

Indofood’s controversial palm oil practices have driven away 15 business partners over the past 2 years, including Nestlé, Wilmar, Musim Mas, Cargill, Fuji Oil, Hershey’s, Kellogg’s, General Mills, Unilever, and Mars. Indofood’s CEO, Anthoni Salim, has also received scrutiny for his other palm oil businesses that are operating in the shadows and illegally clearing substantial areas of peatlands in Borneo or embroiled in serious land conflicts in West Papua.

The Role of Banks

Given Indofood’s market share, it’s no surprise that multinational banks and investors are attracted to the company. In fact, banks have financed one third of Indofood’s palm oil expansion capital. But any amount of due diligence would reveal that this company’s operations are rife with illegalities, human rights abuses and environmental harms that should turn away any responsible bank or investor. So which banks have taken steps to mitigate these risks and which banks are continuing to facilitate Indofood’s Conflict Palm Oil practices?

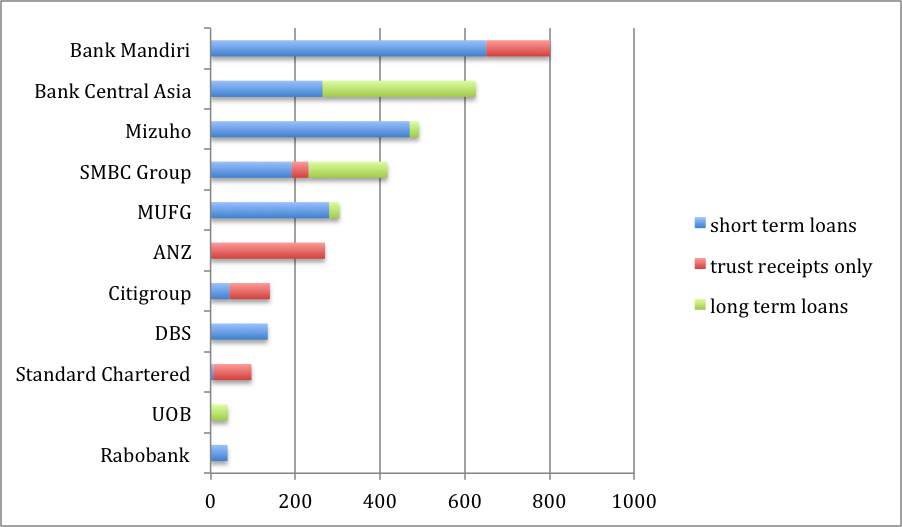

As of March 31 this year, Indofood’s largest financiers included Indonesian banks Bank Mandiri and Bank Central Asia, followed by the three largest banks in Japan – Mizuho Financial Group, Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group (SMBC Group) and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG), the parent company of San Francisco-based Union Bank. Among Western banks, ANZ and Citigroup have the greatest exposure, followed by Rabobank and Standard Chartered. Singaporean banks DBS and United Overseas Bank lend to Indofood as well. (See below)

Bank Loans and Trust Receipts to Indofood & Subsidiaries

(Maximum Credit Facility Limits, Unit: Million USD)

Source: Indofood Financial Statement March 31 2019

Following Indofood’s RSPO termination, several Western banks have cut ties with Indofood or cancelled substantial loans. In June, Standard Chartered exited its client relationship with Indofood, while Rabobank stopped lending to Indofood’s palm oil operations. In May, Citigroup cancelled a $140 million revolving credit facility to Indofood and divested from the company in its entirety. Standard Chartered, Rabobank and Citi’s financing policies require clients to comply with host country laws and regulations, be RSPO members, and commit to a time-bound action plan to achieve RSPO certification. Indofood was clearly in noncompliance with these policies since March. Evidence of Indofood’s labor abuses had already prompted Citi to stop lending to Indofood’s palm oil operations in April 2018, while Deutsche Bank stopped lending to Indofood in 2017. Rabobank has justified their continued relationship with Indofood on grounds that they now ring-fence their financing to non-palm oil operations, but this is a flawed mitigation strategy given the fungibility of money and, in this instance, evidence of weak corporate governance by Indofood that include multiple violations of Indonesia’s 1999 Anti-Monopoly Law by Indofood’s subsidiaries. Rabobank not only finances Indofood, but also maintains a cosy relationship with its CEO Anthoni Salim through Salim’s participation on Rabobank Asia’s Food & Agribusiness Advisory Board. In stark contrast, ANZ and DBS, both prohibit financing of clients engaged in labor exploitation in the palm oil sector, but continue to lend millions of dollars to Indofood.

Equally concerning is the substantial financing by Japanese and Indonesian banks. While neither Bank Mandiri nor Bank Central Asia have dedicated policies on the palm oil sector, all three Japanese megabanks recently adopted policies that require palm oil clients to operate legally and sustainably, in varying degrees. While lacking in detail, these policies should rule out any further financing of Indofood. SMBC Group in particular stipulates that they “will not provide financial support to Palm Oil plantation companies that are involved in … human rights violations such as child labor”; and they “will check that internationally accepted external certifications such as RSPO or other equivalent certifications are obtained or expected to be obtained.” Starting in July, MUFG will “request clients to submit action plans to achieve [palm oil] certification” with a preference for the RSPO, while Mizuho states that it will “take into consideration whether the client/project has received certification for the production of sustainable palm oil.” Despite these commitments, all three banks continue to finance Indofood with hundreds of millions of dollars.

The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises makes clear that banks have a responsibility to prevent or mitigate actual or potential adverse impacts on issues such as labor exploitation that are directly linked to the bank’s clients. Where the harms are foreseeable, the Guidelines indicate that banks may even be implicated in contributing to the harms, in which case they are responsible for remediation. As OECD banks, ANZ, Rabobank and all three Japanese megabanks risk violating these Guidelines as well as their global reputation. Indofood’s unsustainable business model and market risks should also worry banks on financial grounds.

The Role of Investors

While banks are the dominant source of capital for Indofood, institutional investors also play a role in facilitating Indofood’s Conflict Palm Oil by accounting for 10% of its palm oil expansion capital. According to the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, investors also have a responsibility to mitigate the harms, even when they have a minority stake.

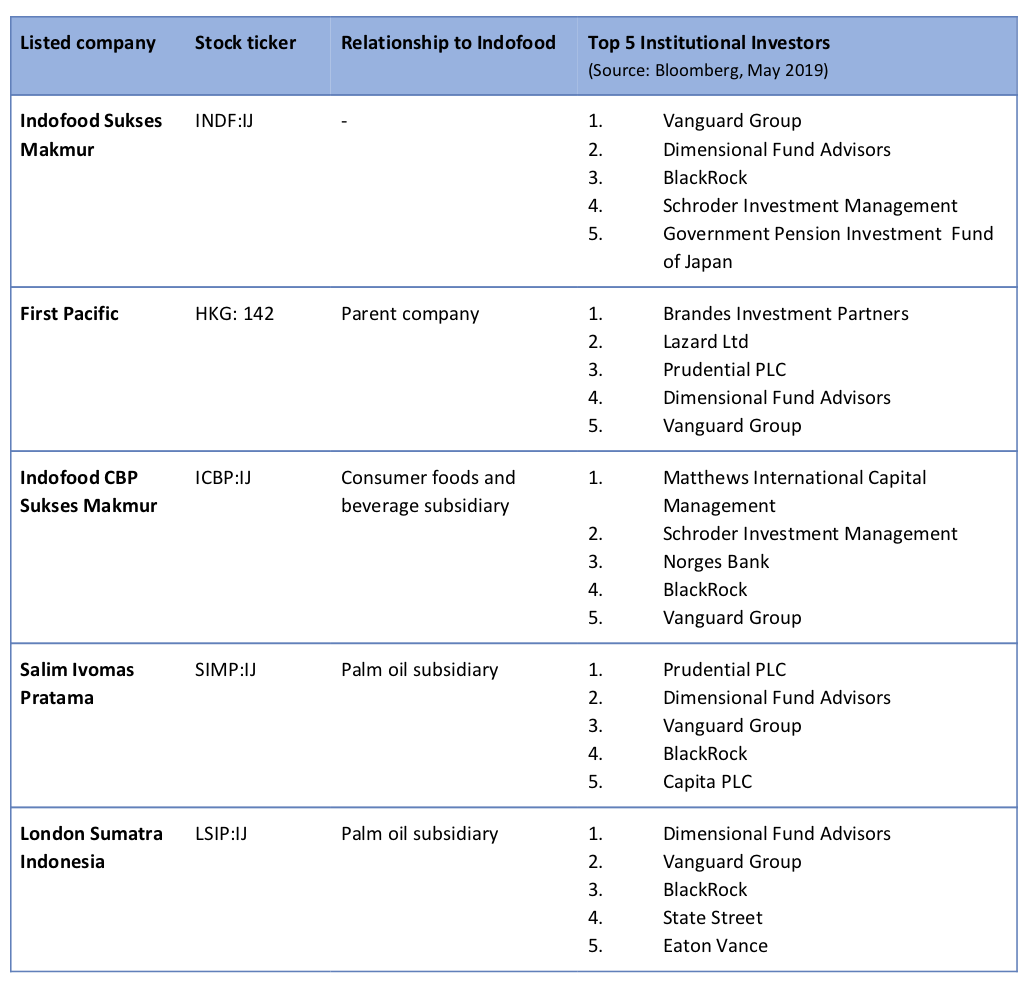

Investors have exposure to Indofood’s ESG risks through Indofood and several related publicly listed companies. Below is a list of the top 5 institutional investors for each of these companies.

In general, the response by investors has been disappointing and contradictory. One of the first to publicly divest from Indofood was the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global (Norges Bank), the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund. It withdrew its investments from Indofood Agri Resources and First Pacific because they “were considered to produce palm oil unsustainably.” However, as indicated above, they continue to be invested in Indofood CBP, which relies on Indofood’s Conflict Palm Oil for production of packaged products. In 2016, Dimensional Fund Advisors removed all palm oil companies from two of its sustainability portfolios, which included a subsidiary of Indofood – Indofood Agri Resources (which recently went private). But Dimensional’s other funds continue to be heavily invested in Indofood. Meanwhile, BlackRock’s CEO has called on all of its investee companies to make “a positive contribution to society” and to “benefit all of their stakeholders.” That should necessitate rigorous time-bound engagement with and likely divestment from Indofood.

In April of this year, 56 investors affiliated with the UN-supported Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), with approximately $7.9 trillion in assets under management, highlighted their support for the RSPO and called for all companies across the palm oil value chain, including producers, refiners, traders, consumer goods manufacturers, retailers and banks, to adopt and implement a publicly available No Deforestation, No Peatland and No Exploitation (NDPE) policy and achieve full traceability of palm oil to the plantation. While none of these investors are among the top five investors of Indofood or its related companies, some are minority shareholders, and many hold shares in the banks mentioned above as well as in Indofood’s prominent joint venture partner PepsiCo. Indofood’s policy falls short of the NDPE standard as it fails to apply at a corporate group level, and lacks explicit requirements to protect High Carbon Stock forests using the High Carbon Stock Approach or comply with international human rights norms. Among its bankers, only Standard Chartered, Rabobank, DBS, and ANZ have explicitly incorporated NDPE into their policies. Investors need to ensure sustainable palm oil by demanding better policies and practices that are aligned with NDPE.

Recommendations for banks, investors, and regulators

Institutions providing financial services to Indofood and the wider Salim Group share a responsibility for the harmful environmental and human rights impacts resulting from its palm oil operations. Banks and investors can and should use their leverage to demand the following of Indofood and other Salim Group companies:

- A publicly available time-bound implementation plan that addresses the labor abuses identified by the RSPO;

- Establishment of a credible grievance mechanism that is aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and independently verified corrective actions to remedy documented labor violations and existing land conflicts;

- A commitment to immediately cease all new plantation development until compliance with the requirements of the High Carbon Stock Approach is verified and investment is made in the restoration of the degraded peatlands; and

- Adoption of a comprehensive NDPE policy that applies to the entire Salim Group, including Anthoni Salim’s shadow companies, as well as all third party suppliers.

Banks and investors should ensure that their continued financing of Indofood is contingent on satisfaction of these demands, and where that’s not possible, to divest from the company as Citi and Standard Chartered have done. Regulators should ensure that banks and investors are properly disclosing these risks in their portfolios, rigorously addressing them, and reporting on progress to all relevant stakeholders. Indofood should be considered an important litmus test for the financial sector’s commitment to sustainability.