Chevron is pioneering a technology that enables the oil giant to better exploit what’s left of the world’s dwindling oil supply — and as you might imagine, that technology is designed to maximize Chevron’s profits even at the expense of people and the planet.

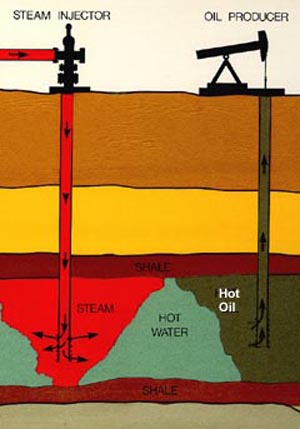

“Steamflooding” or “steam injection” is a technology that involves injecting super-heated steam into oil wells in order to soften up thick, heavy crude oil and make it easier to suck out of the ground (heavy crude can be as thick as molasses and is much more difficult to pump out of the ground than light crude).

Tragically, steam injection might have contributed to the death of a veteran Chevron oil field worker, 54-year-old Robert David Taylor, who fell into a sinkhole full of steam and water while he and three co-workers were walking across a Chevron drill site in Southern California earlier this month. Cal-OSHA is currently investigating Taylor’s death.

Always seeking to minimize the cost of human life exacted by its business operations, Chevron’s spokeswoman, Carla Musser, described the nightmarish scenario to The Bakersfield Californian like this:

“As the employees walked through the site, the ground beneath one employee gave way,” Musser wrote in an email. “The employee fell several feet below ground level into a hole that contained steam and hot water. Efforts to help the fallen employee were not successful.”

This is hardly the first time a Chevron worker has paid with his or her life for the oil giant’s reckless pursuit of profits. Just last month, in fact, four workers died in an explosion at a Chevron refinery in Wales. However, the under-reported death of Robert David Taylor deserves to be more widely exposed and scrutinized.

The process of injecting super-heated steam into the ground can be extremely dangerous. In this case, it appears to have contributed to the weakening of the ground on which Taylor and his colleagues were walking. And though the steam is injected deep underground, it can and often does find its way to the surface, where it wreaks havoc on plants and wildlife. Chevron downplays the severity of what it euphemistically refers to as “surface expressions,” but it’s high time some really tough questions were asked of the company.

Chevron has been using steam injection for decades at some of its oil wells in Kern County, California. The biggest question is: What types of “surface expressions” has the company seen at its steam injection sites, how frequent are they, and how destructive are they?

Chevron CEO John Watson recently smirked his way through a Wall Street Journal interview in which he insisted that peak oil was not something us regular people need to concern ourselves with. Despite all evidence to the contrary, the world’s supply is in no danger of disappearing, Watson said, because technological innovation keeps making new sources of this finite fuel supply open to exploitation. (Never mind the fact that this argument implicitly accepts the premise that all the easy-to-reach oil is running out and hence actually supports claims that we might have already reached peak oil.)

Presumably, steam injection is one of the technologies Watson was talking about. Chevron’s experience with steam injection led to the company’s partnership with Saudi Arabia, whose light crude reserves have all but run out. The Saudi royal family has turned to Chevron to help exploit its reserves of heavy crude oil in order to maintain a steady flow of American dollars into their bank accounts. But what price are the rest of us willing to pay to reach the last reserves of oil we have left? Are we willing to keep ourselves hooked on dirty energy so people like John Watson and the Saudi royal family can make themselves richer while destroying the environment and disregarding basic human rights? Doesn’t it make more sense to invest in safe, sustainable alternative energy sources instead?

However we might answers those questions as a society, it appears Chevron is determined to use whatever technology it can to suck every last drop of crude oil out of the bowels of the Earth, despite the cost to the environment and the climate — let alone human life.