This is an opinion piece by RAN Energy Finance Campaigner, Mary Lovell.

Last month, I had the honor and privilege of joining 25 grassroots organizers for the 600-mile Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe’s Bridge to the Ancestors run – led by Youth from Standing Rock and Cheyenne River. These Youth runners led grassroots campaigns against the Dakota Access Pipeline, raising awareness in their run from Omaha to DC in 2016. They collaborated to organize a run with the Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe, who are facing similar impacts of resource extraction and colonization through oil and gas, specifically fracking and large liquefied “natural” gas (LNG) – aka methane gas – terminals proposed on their lands.

I was humbled to see places of destruction and sacred sites, have genuine friendship, and gain an understanding of how things feel and look on the ground.

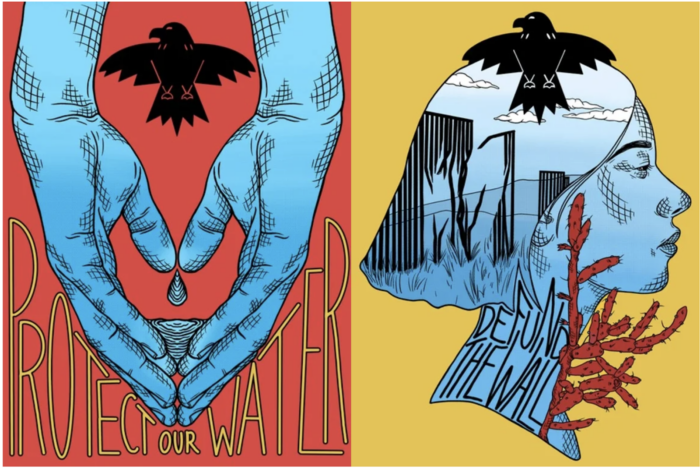

The Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe of Texas is a leader in resisting extractive industries of all kinds: from oil and gas to Space X and border wall construction. They are rare birds in West Texas to be outspoken social justice activists in a land stolen from their community. This community has filed countless lawsuits, led land defense blockades, met with large international banks and investors, influenced federal regulatory processes, led human rights tribunals, and tried every strategy that may defend their land from the encroaching resource extraction and exploitation of communities.

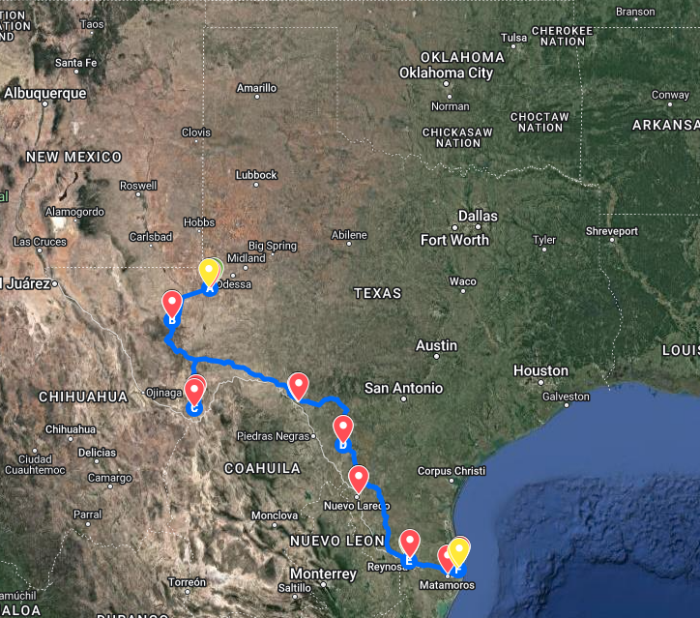

As a community, the Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe wanted to organize a relay run to connect their people and land. Together, we relay ran an ancestral walking and running route of the Carrizo Comecrudo all the way from the Permian basin (Midland, Texas to Brownsville, Texas) to the Gulf of Mexico — the same route as the lifecycle of LNG in the US before being exported, shipped, and burnt around the world.

This run was along the route of the US-Mexico border, which separates families to this day. In the borderlands, folks are fighting intense human rights violations, including surveillance, detention, murder, and abuse.

This landscape and its people are new to me. As a rainforest dweller in coastal Washington, I was struck by the realities of the heat, the long stretches of industry, the multicultural reality of southwest Texas, and the poverty and policing that folks are facing every day. I am new to working in this region, and it felt like an incredibly important honor.

Starting from the beginning: The Permian

In the city of Monahans, lies a mystical place where the wind sculpts sand dunes into peaks and valleys, sometimes overnight. Waking in the sand with the wind pushing the landscape around, with a crunch of sand between the teeth. Small footprints of every type of wildlife danced through the sand, erased and reappearing by the wind.

Excited and nervous – we started the run in Monahans as the heat washed down on us. We began with a prayer, and the group saw a shooting star before we took off down the road, one person running, and switching out, finding a rhythm of how many miles we could do. The Youth leading the run drank pickle juice to restore salts, and we cheered them at each stop.

The next day, the air quality was so bad that we had to stop running. My lungs hurt from running just half of a mile, and I was coughing through the rest of the day — the gas leaking from the Permian oil and gas wells is ever-present and lingering.

Big Bend

From there, we dropped down into the canyons and rocky regions in Big Bend to see some of the most beautiful landscapes. We also gathered volcanic rocks that the community uses in a ceremony for a sweat lodge. There were lots of militia in this area, bothering us when we stopped — they’re there to menace immigrant communities, “defending” the state from who they see as a threat.

Underneath a starry sky, we shared a fire and stories, laughing late into the night. As we curled up into our tents, we listened to a chorus of yips — coyotes singing in the night, celebrating a good hunt.

Balmorhea

In the Balmorhea region, we went to see a sacred spring that’s provided water to people crossing through the region for tens of thousands of years. This region is being impacted by the Saguaro pipeline proposal, a fracked gas pipeline proposal that would push gas across the US into Mexico for export.

Late at night, exhausted and exhilarated from a long day running, we drove a winding and beautiful road under bright starry skies, as wild boar raced across the road.

We went to see the Marfa lights, where the Carrizo believe the spirits pass on. The lights are incredible and otherworldly. Listening to Christa Mancias singing to the lights and seeing the lights dance in response is a moment that I will never forget.

In the next stretch, there were many caves and village sites, including a cave called Los Cuevitas. Los Cuevitas was home to a fire for many years by the community, where it was kept alive and folks would use to light other fires in the region.

We also stopped to learn about different plant medicines and to harvest some of them and learned to process a fox for her hide.

Laredo and the home of the Monarch

From there, we went to Laredo. We ran past a memorial of a young woman who was killed by ICE. Seeing the surveillance, intimidation, border checkpoints, militarization, and human lives lost in this region was heartbreaking.

We had a community forum with about 30-40 folks attending and speaking about the impacts on their land and their communities — and we saw three separate people being detained and incarcerated by border patrol.

The following morning, I woke up and walked along one of the only lakes in the region, glimpsing beautiful birds, lichens, and cypress trees. We visited the Butterfly Center that is fighting the border wall where the community had asserted their rights through a temporary village site of 7 months. Unfortunately, the wall was still built, and the owner has received many death threats for her work. There are 13 Indigenous village sites in this region.

Little kids joined as as we ran from the Butterfly Center in the hot sun, including a ten-year-old boy ran more miles than anybody else. He has a heart condition, and his mom couldn’t stop smiling, talking about how rare it is to see him break out of his shell.

Grave sites and border destruction

We visited a grave site that was another Carrizo Comecrudo village site, re-asserting sovereignty that was defending against the border wall. The wall and levy were constructed without any regard for the bones of the community’s ancestors, even though the grave site is well-marked. They were able to hold off construction for over a year by living on their land.

Boca Chica, playing in the gulf and space colonization

We ended the day by visiting a beach called Boca Chica, a beautiful sacred site on the ocean. The Youth got to play in the ocean for the first time, and the runners were laughed and smiled in the windy ocean.

The small beachside community that used to live here has been pushed out for the construction of Space X. The town of Brownsville is surreal as there are literally murals of Elon Musk paid for by himself. Space X is gentrifying Brownsville and the surrounding area with high-paid workers, shutting down local businesses. The Space X facility they constructed is huge, and a few weeks back, their first test exploded — blowing toxic materials all over the region.

Garcia Pasture and RGV

We ran near Garcia Pasture, a site in the register of historic places, a cultural village site, and an archeological site where two large LNG facilities are proposed — Rio Grande LNG and Texas LNG. Garcia Pasture is “a pre-Columbian village dating to between 1000 and 1750 CE. This cultural landscape hosts human burials, village ruins, rock art, and shell working areas, as well as diverse wildlife, plant life, and the rich legacy of some of the first North American human inhabitants.”

We had a community forum where 50-60 people came together, organized by Bekah Hinjosa. Bekah’s community is fighting two LNG facilities, and when the most recent Space X rocket exploded, her home and her community was rocked by the impact.

Learn more: watch the PBS special about the run here.