Brands Fail to Enforce Ban on Destruction of Peatlands for Palm Oil In Orangutan Capital of the World

A year after releasing the Carbon Bomb Scandals report at the start of Climate Week 2022, which exposed major global brands illegally sourcing palm oil produced within the nationally protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve in Indonesia’s Leuser Ecosystem, field teams with Rainforest Action Network have collected fresh evidence of ongoing and expanded illegal destruction of peat forests inside the reserve. The area being destroyed is a carbon-rich peat swamp and is a globally significant biodiversity hotspot often referred to as the ‘orangutan capital of the world.’ Peatland ecosystems are the most effective terrestrial landscapes on earth for natural carbon sequestration, and, in turn, release catastrophic levels of emissions into the atmosphere when drained and cleared in this way.

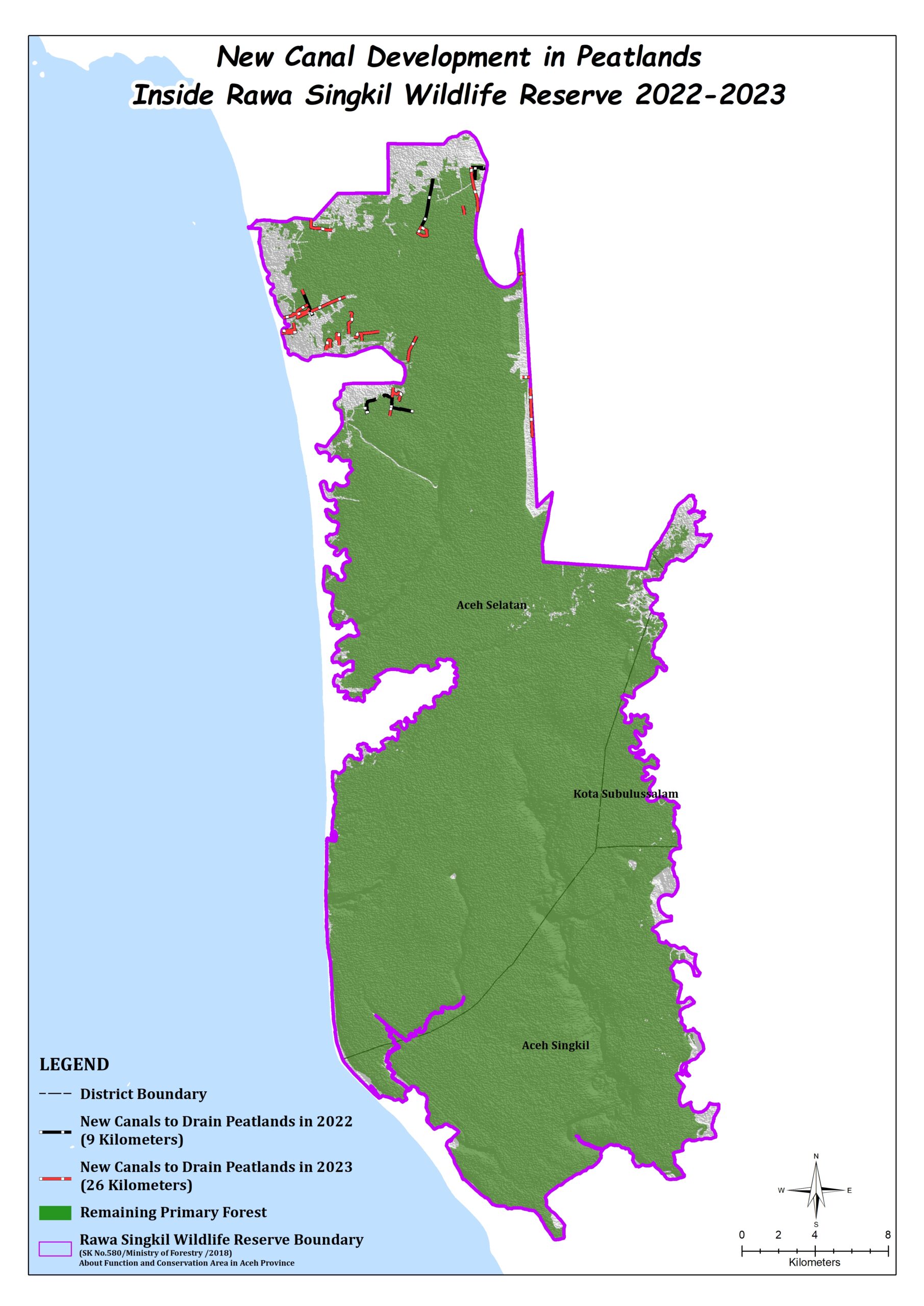

New satellite and drone footage show that at least 26 km of new canals were dug in 2023, up from 9 km in 2022. This increase in new canal development is consistent with worrying data showing an increase in forest loss in the reserve, which is the opposite of trends cited in most primary forests across Indonesia. The driver for the drainage of peatlands via canals is palm oil that will ultimately make its way into the supply chains of international brands, despite these brands having publicly issued commitments against deforestation or peatland destruction. This loophole is due to the inadequate traceability and compliance systems in place by the network of mills surrounding the reserve.

The public policy commitments of major brands have prohibited new development of palm oil plantations on peat since a December 31, 2015 cut-off date. Nearly eight years later, they have failed to stop new development on one the most important peat swamps in Sumatra, home to the highest concentration of critically endangered Sumatran orangutans known to remain anywhere.

The claims made by the world’s biggest brands during Climate Week 2023 about addressing their impact on the climate and ending deforestation and destruction of peatlands in their supply chains simply can’t be trusted. It is crystal clear that the destruction of the primary forests in the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve––a massive store of carbon and the orangutan capital of the world–– persists under their watch.

RAN alleges that the results of its latest investigation demonstrates that local elites with vested interests are fast-tracking destruction within the reserve in an attempt to convince the Indonesian government to reduce the boundaries of the protected area. We know efforts are underway to convince the Minister of Environment and Forestry to change the boundaries of the reserve to once again remove recently cleared areas and existing illegal palm oil plantations from the boundaries of the protected area. This is evident by the decision made by Mr Mahmudin––a local elite who has been caught supplying illegal palm oil to the brands––to backflip on his commitment to return illegal plantations to the reserve for restoration after being exposed in the Carbon Bombs Scandal.

The images below were taken by RAN’s investigators who recently flew drones over the areas of forests inside the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve that are being destroyed by new canal development. A significant area of the new canal development inside Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve is concentrated in the area to the north of the Ie Meudama village, Aceh Selatan. This village was named as the location of Mr Mahmudin’s collection point for illegal palm oil in RAN’s Carbon Bomb Scandals report.

Significant areas of forests are being cleared inside Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve to make way for new illegal palm oil plantations, north of the Ie Meudama village, Aceh Selatan.

The Consumer Goods Forum––and most of the world’s household name brands like Mondelēz, Nestlé, Colgate Palmolive, PepsiCo, and Kao ––have failed to issue any statements detailing the actions they have taken in response to the crisis in the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

During climate week in 2022, RAN’s campaigner Maggie Martin presented the Carbon Bomb Scandals report to the members of the Consumer Foods Forum’s Forest Positive Coalition.

There are 400 consumer goods companies in the CGF. To date, only Unilever, Procter & Gamble and Nissin Foods have issued public responses to the revelations exposed by the Carbon Comb Scandals report. The actions that have been taken by these three brands––and their peers and the Consumer Goods Forum––have not been sufficient given the problems outlined in the report have only worsened over the last year.

Unilever has banned two of the mills RAN exposed for sourcing illegal palm oil––PT. Global Sawit Semesta and PT. Samudera Sawit Nabati––from its supply chain and announced this decision on its suspended supplier list. However, Unilever’s grievance tracker and mill list confirms that it has not banned two other mills implicated in the Carbon Bomb Scandals––PT. Runding Putra Persada and PT. Bangun Sempurna Lestari, so its approach has not been consistent. Unilever also cites its support of landscape programs in Aceh––which have made a positive impact in Aceh Tamiang in the north-east of the Leuser––but these programs have not yet been established in Aceh Selatan where the highest rates of deforestation and new canal development are occuring.

P&G responded to the crisis by committing to work with its suppliers to restore illegal palm oil plantations in the reserve. Unfortunately, P&G remains at risk of sourcing illegal palm oil from its direct suppliers: Apical of the Royal Golden Eagle group, Golden Agri Resources, Musim Mas and Wilmar.

Nissin Foods responded to the Carbon Bomb Scandal in its new grievance list that it published before its Annual shareholder meeting in June. Its response stated that it stopped sourcing from one of the non-compliant suppliers identified in the report––Ibu Nasti––but it did not adopt a No Buy policy for the mill called PT. Bangun Sempurna Lestari that was caught souring illegal palm oil from Ibu Nasti’s illegal plantation within the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

The failure of major brands to respond effectively to such egregious instances of illegality and primary rainforest destruction should be raising alarms across the sector as the enforcement date for the newly enacted European Union Deforestation Regulations (EUDR) are soon to take effect. The EUDR will require all companies importing forest-risk commodities like palm oil into the EU to credibly trace their supplies back to the precise location of their production, and to demonstrate due diligence proving these suppliers are not destroying forests or violating human rights. Continued failure by these brands to achieve these basic acts of verification and traceability will soon expose them and their investors to an even greater material financial risk until they close the loopholes that still exist and truly rid their products of Conflict Palm Oil.