Nestlé, Mars, Mondelēz, Unilever and Dutch bank ABN AMRO found in violation of their own policies against human rights abuses

New field investigations by Rainforest Action Network and documentation by LBH Banda Aceh and Walhi Aceh have uncovered evidence that controversial palm oil company PT. Dua Perkasa Lestari (PT. DPL) has continued to supply Conflict Palm Oil to major brands including Nestlé, Mars, Mondelēz, PepsiCo and Unilever via palm oil giants Golden Agri Resources (GAR) and Permata Hijau, despite PT. DPL’s gross violation of the rights of the Pante Cermin community in Aceh, Indonesia.

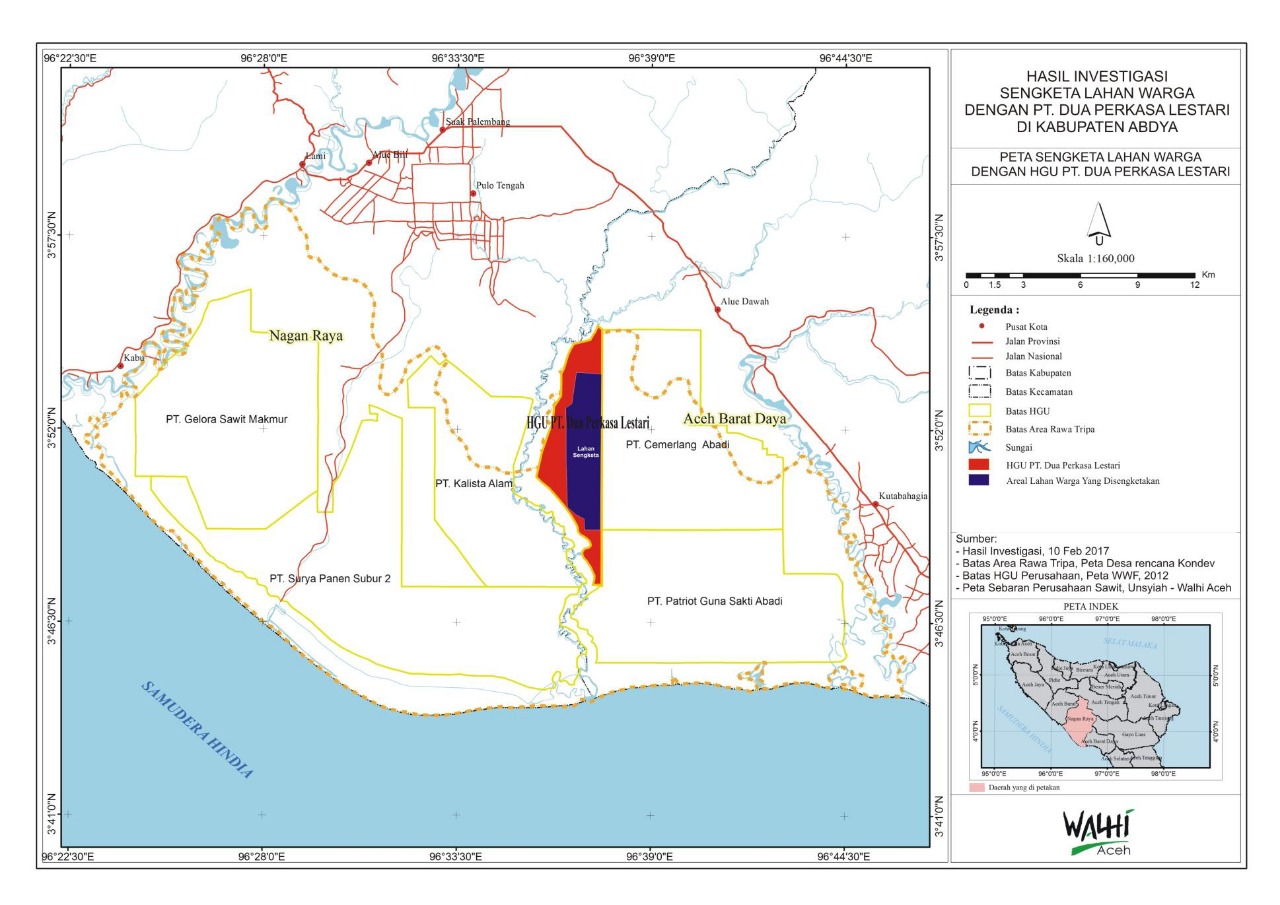

LBH Banda Aceh and Walhi Aceh’s investigation reveals a decades-long unresolved conflict with the Pante Cermin community that includes a lack of proper permits by PT. DPL to operate in the first place, well documented land grabbing of customary lands, destruction of community food crops without Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), and the systematic use of military force to intimidate and displace community members in violation of the policies of Indonesia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs.

The fact that a company like PT. DPL has continued to supply the global market while actively violating the rights of local communities, misusing security apparati to intimidate community members, and ignoring substantial legal problems in its permitting process, means that major brands are not taking their responsibility to implement their “No Deforestation, No Peatland and No Exploitation” policies seriously.

Nestlé, Mars, Mondelēz, PepsiCo and Unilever need to place PT. DPL on a “No Buy” list and engage with their suppliers and PT. DPL to immediately resolve this land conflict as a condition to resume their business. These brands, as well as banks like ABN AMRO and Bank Negara Indonesia (BNI) who continue to finance GAR, must intervene immediately to ensure that GAR adopts a No Buy position for PT. DPL until agreements are in place to return land to the Pante Cermin community members. If GAR fails to do so they must suspend all sourcing from, or financing for, the palm oil giant.

Decades-long community land conflict with PT. DPL

Like many land conflict stories, the community conflict in the district of Aceh Barat Daya is complicated and entangled with Aceh’s own history of conflict with the Indonesian state. One such story is the communities of Pante Cermin village who had to flee from their land in the late 90s due to escalating tension during Aceh’s independence movement. When community members were able to return many years later, they learned that their land was plotted to be given away to palm oil plantation PT. Dua Perkasa Lestari (DPL) without their consent.

History

In 1990, about 60 Pante Cermin community members cleared new land near their village to plant food crops such as rice paddy, corn, peanuts, chilies and jengkol, a flowering tree in the pea family that produces beans native to Southeast Asia. Opening customary land is common in Indonesia and recognized as a customary right under Indonesian Agrarian law. As the community grew, they formed a farmer’s group and divided the land into 2 hectare plots to about 1,000 people in the village. In 1997, the community members each signed a statement letter stating that they are the rightful owners of the plot of customary land and have worked on the land since 1990, co-signed by the head village at the time. These letters in total document the ownership of 2,380 hectares of customary land managed by the Pante Cermin community.

But in 1999 as conflict escalated in the district between the Gerakan Aceh Merdeka (GAM), Aceh’s then separatist movement, and the Indonesian army, these communities fled for their safety, returning seven years later in 2006 when they deemed it safe after a peace deal was made. To ensure their right to the land, the communities initiated a Statement of Physical Ownership of Land, known as a Surat Pernyataan Penguasaan Fisik Bidang Tanah or SPORADIK letter in Indonesian, which was signed and witnessed by the head of the village, the head of the farmer’s group and the Peutua Seuneubok, the Aceh customary chief who presides over customary land rulings. Around this same time, palm oil company PT. Dua Perkasa Lestari sought the land to develop a palm oil plantation and began applying for permits to begin clearing.

Negligent process to seek Free, Prior and Informed Consent from communities

According to Indonesian law and UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, any company which seeks to develop land owned by any community should seek their Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) before development begins and respect the community’s right to accept or refuse development on their land. Instead of conducting participatory FPIC processes, PT. DPL offered the community members IDR 1,400,000 or about less than USD 100 per hectare as compensation for their land. While 20 community members accepted the offer, the vast majority of the community said no. Not long after, the company ignored the ongoing opposition from a majority of the Panten Cermin community and began preparing the land for plantation development. This was a negligent FPIC process that led to the land grabbing of the Pante Cermin community’s legally rightful land and the loss of their source of livelihood.

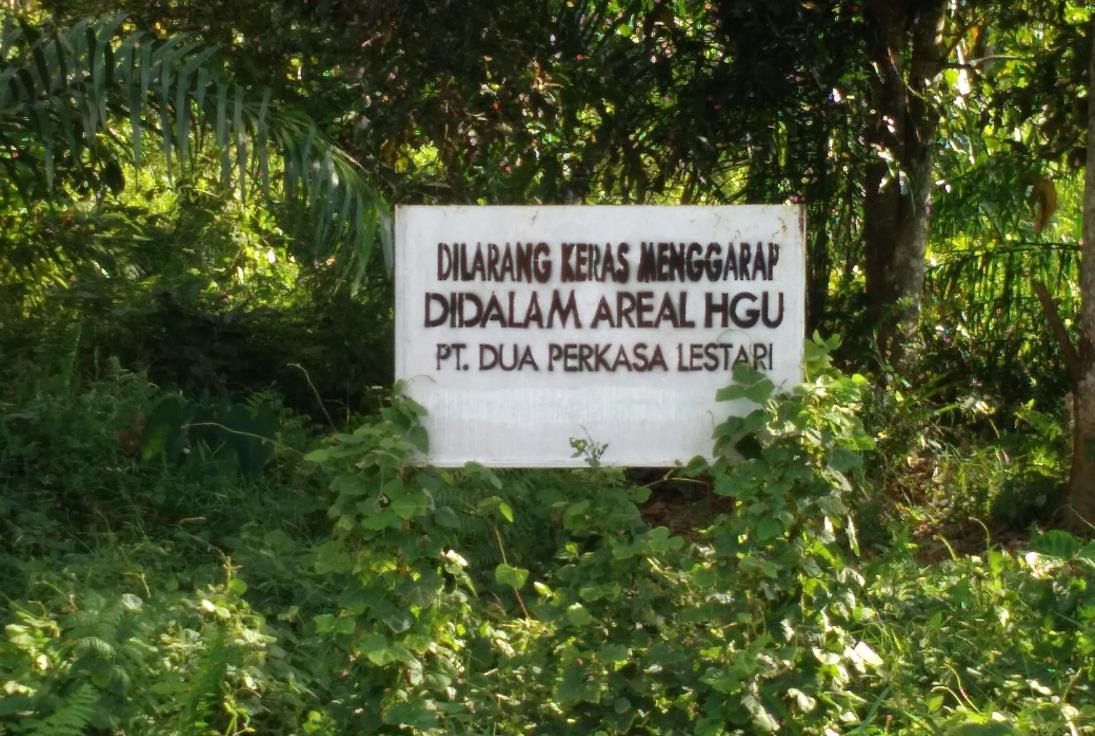

The Pante Cermin communities protested as their established food crops were destroyed. They attempted to reclaim the land that was wrongfully included as part of the company concession, which covered over 2,500 hectares, by occupying the disputed land. The company in response used Indonesian Police Mobile Brigade (Brimob) and the military as guards to intimidate communities and sparked horizontal conflict. Horizontal conflict is where conflict arises between community members, and resulted from the company organizing community members that had accepted the compensation deal to defend the company against other members of the community. One protest in particular in 2014 escalated to an altercation with Brimob that led to a Brimob officer firing a gun right by a community members’ ear. The community member remains traumatized by that incident today. As the conflict ensued, communities’ report that PT. DPL operated their excavators during the night. As community resistance continued, they successfully drove out two excavators while three remain in the area to this day.

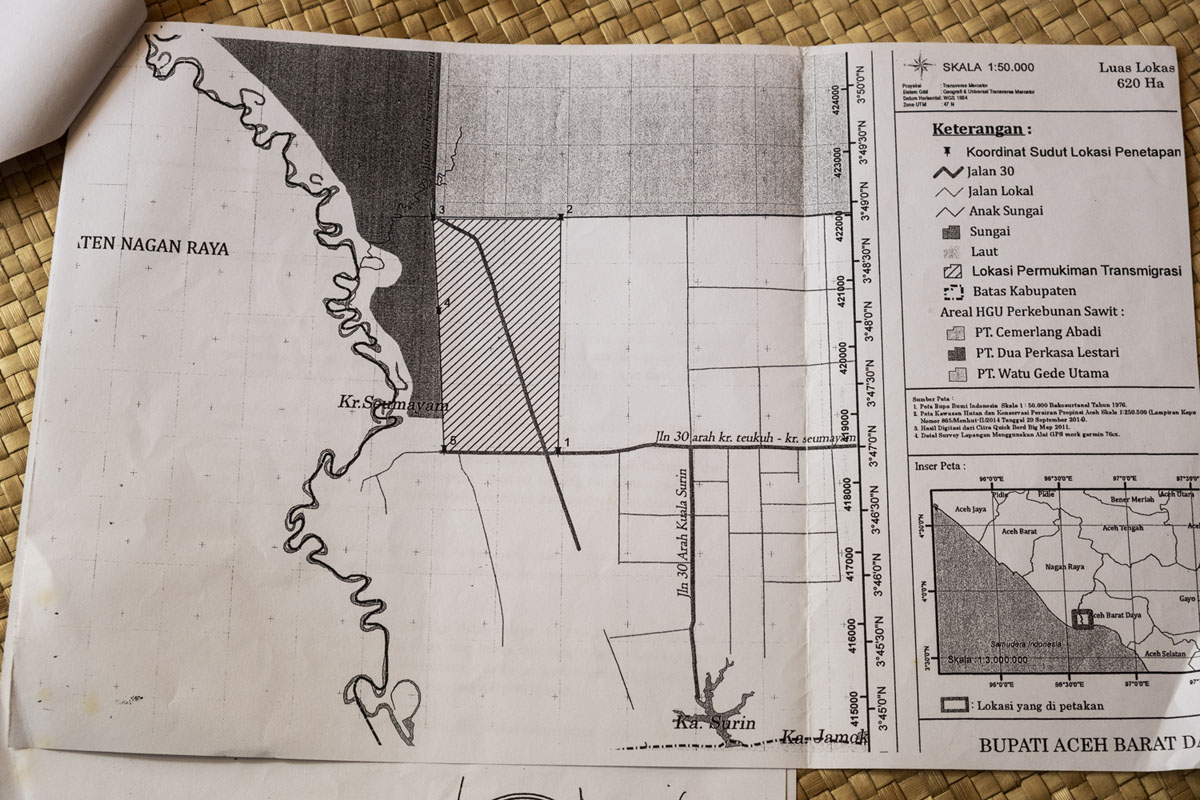

Irregularities in palm oil plantation permitting procedure

A plantation company is required to secure a number of permits before it’s able to operate, mainly a location permit, plantation business license and land use title. Among other things, these permits should state the exact location for the proposed plantation. According to LBH Banda Aceh and Walhi Aceh’s analysis, when PT. DPL began its operation, none of the permits obtained by PT. DPL include the Pante Cermin village as part of its location. In fact, the location permit and land use title state the proposed location is in Ie Mirah village while the location stated on the plantation business license is a completely different village, Krueng Semayam, which is not even part of the district of Aceh Barat Daya. These mismatches in location were reiterated by the head of the sub district and led to community protests as these irregularities mean that PT. DPL does not have the legal grounds to clear and develop their plantation on Pante Cermin community lands but went on to illegally develop it anyways.1

In 2008, the District Head of Aceh Barat Daya requested PT. DPL to stop clearing land for its operation because one of the directors of the company, Said Syamsul Bahri, was concurrently a member of the District House of Representatives, which created a conflict of interest in violation of Indonesian Law.2 In 2015, the District Head sent another letter requesting the company to stop land clearing as it has yet to secure recommendations from both the Forestry Agency and Aceh’s Integrated Licensing Service Agency.3 In 2015, the area where PT. DPL started clearing was also designated as a transmigration settlement area, a government program to resettle people from densely populated areas of Indonesia to less populous areas in the country, becoming yet another contradiction to PT. DPL’s licenses.4

A verification team formed by the Head of Aceh Barat Daya District in 2011 found that some of the lands were managed by communities with crops that were evidently planted for the past five years. This evidence was enough for the government to recommend for PT. DPL’s permit to be revoked.5 A few farmers’ groups, allegedly backed by the company, came to PT. DPL’s defense and requested for the revocation to be dropped.

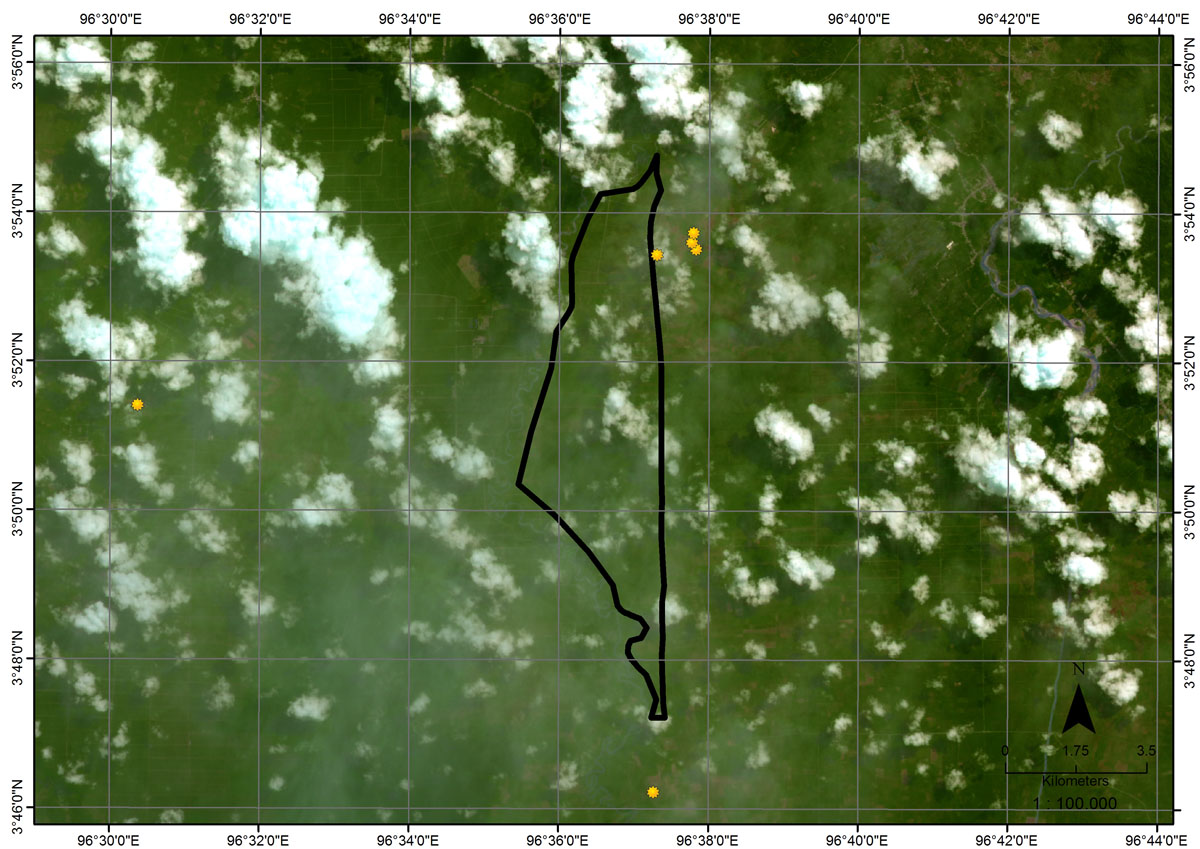

Development on peat

By superimposing PT. DPL’s Land Use Title (HGU) area with the Leuser Ecosystem map, spatial analysis revealed that the whole area of PT. DPL is located within the globally important Leuser Ecosystem. Based on the stipulation of the National Peat Ecosystem Function in accordance with the Decree of the Minister of Environment and Forestry Number SK.130 / MENLHK / SETJEN / PKL.0 / 2/2017, it was identified that 1,819.3 ha (70%) of PT. DPL area is located within the Cultivation Function Zone, whilst 779.7 ha (30%) of the area is located in the Protected Function Zone. The latter is a peat area identified for restoration by the government.6

Field investigation in 2017 by Walhi Aceh and Pante Cermin community members found the disputed land to be on peat of 2.5 meters depth. The land was already cleared and canals were apparently made to drain the peat.

Use of military to silence communities

As PT. DPL cleared the land for development, the company involved military personnel (Brimob) to guard the area, deter opposition and forcefully evict community members that stood in their way. With the presence of military personnel, community members were afraid to return to their land and a number of altercations led to the military firing guns in the air, intimidating communities further. This type of use of military force is in clear violation of a Circular Letter from Indonesia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs that prohibits the use of military personnel to evict or clear community owned lands.

The urgent need to return land to community members

Currently, 50 community members continue to resist forceful eviction and after careful verification by LBH Banda Aceh so far, 400 people still have credible documentation of their rightful ownership to the land. Only a small portion of them have continued to reclaim their land as they are constantly at risk of intimidation by police forces that still patrol the area. In their effort to seek remedy for the land conflict, along with LBH Banda Aceh and Walhi Aceh, communities have reported their grievance to the local, provincial and national government as well as the Aceh Barat Daya District House of Representatives. The Pante Cermin communities continue to demand their land back and that the government revokes the improper permit used by PT. DPL and return their land.

Exposed: Conflict Palm Oil from PT. Dua Perkasa Lestari found in the supply chain of major brands.

Rainforest Action Network’s field investigators have uncovered evidence that PT. DPL has continued to supply palm oil to major brands Nestlé, Mars, Mondelēz, PepsiCo and Unilever via palm oil giants Golden Agri Resources (GAR) and Permata Hijau, and secondary traders including AAK, ADM, Bunge Loders Croklaan, Cargill and Fuji Oil, despite its gross violation of the rights of the Pante Cermin community. A palm oil mill listed in the published mill lists of these major brands and traders, operated by PT. Beurata Subur Persada, was caught accepting palm oil fruit from PT. DPL. Despite the No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) commitments of these major brands, they have failed to ensure that their supply chains are free of exploitation and rights abuses.

A pile of palm oil fresh fruit bunches is gathered for collection in PT. DPL’s concession.

A truck carrying fruit bunches from PT. DPL’s concession enroute to PT. Beurata Subur Persada’s palm oil mill.

The same truck from PT. DPL arrives to deliver oil palm fruit for processing at PT. Beurata Subur Persada’s mill.

The fact that a company like PT. DPL has continued to supply the global market while actively violating the rights of local communities, misusing security apparati to intimidate community members and guard its concession, and ignore legal problems in its permitting process, means that major brands are not taking their responsibility to intervene and implement their “No Deforestation, No Peatland and No Exploitation” policies seriously. Their continued purchasing of palm oil from PT. DPL via PT. Beurata Subur Persada only cements business-as-usual practices that ignore these problems and continue palm oil development on stolen lands. Nestlé, Mars, Mondelēz, PepsiCo and Unilever need to place PT. DPL on a “No Buy” list and engage with their suppliers and PT. DPL to immediately resolve this land conflict as a condition to resume their business.

Failure of Brands and Banks to ensure Golden Agri Resources upholds its Human Rights Commitments.

This case further demonstrates the failure of brands and banks to ensure that GAR implements its “No Exploitation” policy commitments and intervenes to secure long term solutions that resolve land conflicts and protect and restore Aceh’s peatlands. Since 2016, GAR has known that its supplying mills located inside and around the Tripa peatland, including PT. Beurata Subur Persada, source from PT. DPL despite its violation of the rights of local communities and the clearing of over 2000 hectares of forested peatlands in an area once known as the orangutan capital of the world. GAR’s field verification report confirmed that PT. BSP’s mill lacked adequate traceability systems to ensure they were not accepting oil palm from illegal sources and PT. DPL, and set a deadline for the company to establish traceability systems by the end of 2018. GAR’s decision to continue sourcing palm oil from PT. DPL despite its failure to return land to rightsholders in the Pante Cermin community, and PT. BSP despite its failure to establish traceability systems by the deadline it set, shows a systemic failure in GAR’s efforts to achieve NDPE compliance by palm oil mills and producers located in the Leuser Ecosystem.

GAR’s public grievance list cites the adoption of a commitment in February 2020 not to clear the remaining standing forest in its concession, approximately 104 hectares, as a reason for resuming sourcing from PT. DPL but lacks any information on requirements set for PT. DPL to resolve conflicts with the Pante Cermin community. Brands sourcing from GAR must intervene immediately to ensure that GAR adopts a No Buy position for PT. DPL until agreements are in place to return land to the Pante Cermin community members. If GAR fails to do so each brand must suspend all sourcing from the palm oil giant.

Major global banks, including some that have lending policies that prohibit lending to clients involved in the violation of human rights, continue to finance the Sinar Mas Group despite its failure to respect human rights in its own operations and those of its third party suppliers like PT. Dua Perkasa Lestari. Sinar Mas Group is a group of companies controlled by the Widjaja family, including its palm oil entity Golden Agri Resources. Sinar Mas’ palm oil divisions received in excess of USD 3.5 billion in loans and underwriting for the period 2016 – April 2020 (the same period where evidence of human rights violations and deforestation by PT. DPL was raised with GAR). Some of the largest lenders for this period include China Development Bank (USD 520 million), Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (USD 508 million), Bank Negara Indonesia (USD 438 million), CIMB Group (USD 271 million), and ABN AMRO (USD 226 million). These banks must also intervene immediately to ensure that GAR adopts a No Buy position for PT. DPL until agreements are in place to return land to the Pante Cermin community members.

During a time full of uncertainty with the pandemic looming over our collective future, access to land and food sovereignty will make or break communities like Pante Cermin. Being able to live off their land can extend the livelihood of the community while mobility, jobs and the economy are disrupted. Securing their land rights provides for a much more lasting solution for future climate-induced crises. It is more urgent than ever for the Pante Cermin land conflict be resolved and for their land to be returned to the rightful ownership of the community.

End Notes

- Statement Letter by Head of Subdistrict (Surat Pernyataan Camat) Babahrot, Agussalim, S.Pd, No. 522.11/SP/BBR/2010. August 2010.

- Letter by Head of Aceh Barat Daya District No. 522.12/ /2008 regarding the Prohibition of Opening Plantation Area in Gampong Krueng Seumayam Kecamatan Babahrot. June 2008.

- Letter from Head of Aceh Barat Daya District to the Director of PT. Dua Perkasa Lestari No. 525/287/2015 regarding the Cessation of Land Clearing Activity. March 2015.

- Head of Aceh Barat Daya District Decree No. 674 Year 2015 on the Transmigration Settlement Location. October 2015.

- Letter from Head of Aceh Barat Daya District, Jufri Hasanuddin, No. 525/655/2012 to Aceh Governor, Zaini Abdullah, on the recommendation to revoke the concession permit (HGU) of PT. Dua Perkasa Lestari. September 2012.

- Golden Agri Resources. Verification Visit re Grievance submitted by Rainforest Action Network (RAN) against PT Dua Perkasa Lestari (PT DPL) in Aceh. November 2016. Link here