Indonesia’s largest food company, Indofood Sukses Makmur (Indofood), has been under increasing scrutiny since 2016 for its egregious violations of human rights linked to its palm oil operations. Indofood is part of a complex network of companies called the Salim Group, whose CEO Anthoni Salim is also CEO of Indofood and the fourth richest person in Indonesia. Aside from the human rights abuses, companies indirectly controlled by Anthoni Salim were recently exposed for illegally clearing nearly 10,000 ha of carbon-rich peatlands in Indonesia over the last 5 years, now releasing the equivalent of more than 1 million tons of new and additional CO2 emissions every year. This is roughly the same as burning 2.3 million barrels of oil.

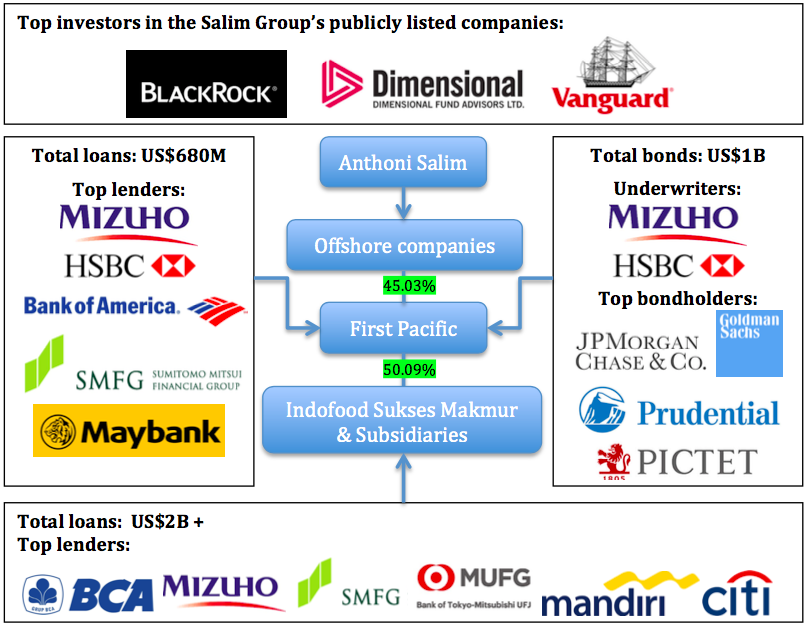

Despite these problems, many banks and investors who claim to be socially and environmentally responsible are financing Indofood and the wider Salim Group with billions of dollars. These include well-known companies like Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, BlackRock, and Vanguard, as well as major banks located in Japan and Indonesia like Mitsubishi UFJ, the parent company of Union Bank. Citi, to its credit, recently cancelled its loans that directly supported Indofood’s palm oil plantation activities.

While more banks and investors are recognizing the importance of “Environmental Social and Governance” (ESG) factors in their financing decisions, Indofood is a perfect microcosm of how too many are failing to address the real human and ecological consequences of their financing.

ESG risks in the forest-risk commodity sector and financier exposure

Southeast Asia has one of the largest remaining rainforests in the world, but rapid deforestation continues, largely driven by a handful of commodities including palm oil, pulp & paper, timber, and rubber (hereinafter “forest-risk commodities”). These forest-risk commodity sectors face significant ESG issues including climate change, biodiversity loss, land grabbing, labor abuses, bribery and illegal activity. These have direct implications for the financial sector, as they give rise to material risks like work stoppages, canceled contracts from buyers, and litigation, and can ultimately harm financiers as a result of client default on loans and negative returns on investment as well as reputational risks for the financiers themselves, to name a few. (For more details, see RAN’s Every Investor Has A Responsibility report)

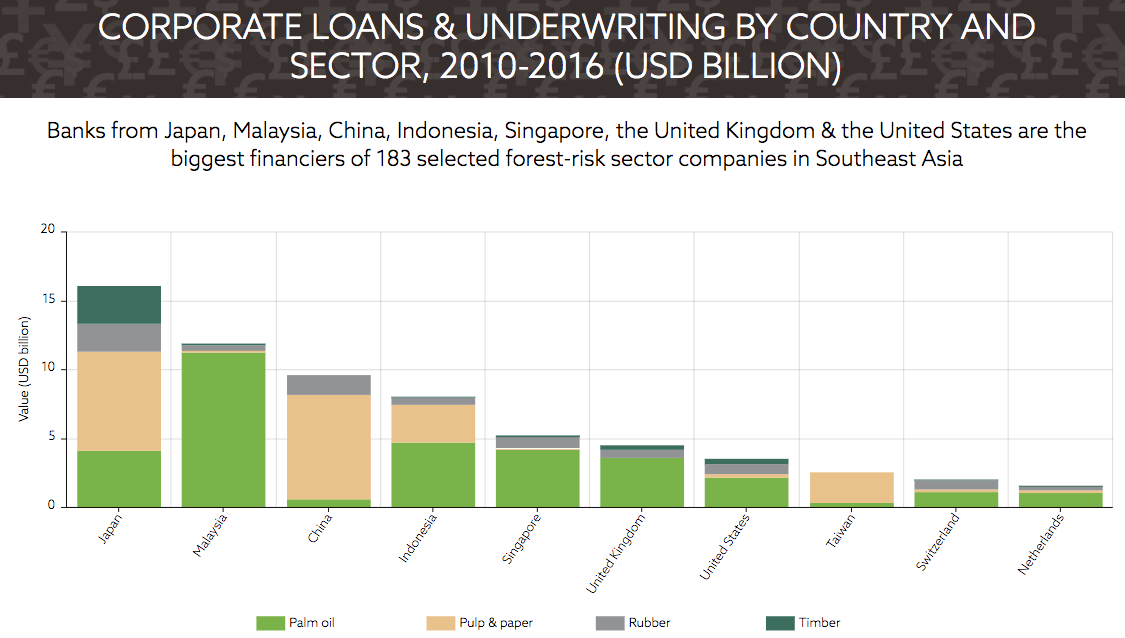

Despite these risks, research by forestsandfinance.org found major banks and investors, particularly in Asia, are making substantial investments in this sector, including in companies with egregious ESG risks like Indofood. (See Below)

Source: forestsandfinance.org

Source: forestsandfinance.org

ESG Risks of Indofood & Associated Companies

Indofood’s ESG risks from its upstream palm oil investments should concern any financier. Some of the more significant risks include:

- Labor abuses: There is evidence of systemic violation of 20 Indonesian labor laws, including use of child labor, hazardous working conditions and payment below minimum wage. These labor abuses were first exposed in June 2016, and confirmed multiple times, including by RAN and our partners in November 2017 and twice by an independent auditor, including as recently as March of this year.

- Violations of RSPO certification standards: Indofood’s palm oil subsidiaries are being investigated by the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) on allegations of labor exploitation, with the risk of suspension. The RSPO suspension of palm oil grower IOI led to an exodus by 27 buyers and a drop in the share price by 20%. PepsiCo, a major joint venture partner for Indofood, recently suspended direct purchases of palm oil from Indofood’s palm oil subsidiaries, and other buyers, including Kellogg’s, General Mills, Mars, Hershey’s, and L’Oreal, are also moving to reduce their exposure. An RSPO audit is now scheduled for June of this year, and 100 investors representing $3.2 trillion assets under management have publicly declared that they are paying close attention.

- Contested land: 42% of IndoAgri’s plantation landbank, equivalent to 230,700 ha, is contested as a result of community conflicts, labor controversies, environmental regulations that restrict development, or undisclosed concession maps. Chain Reaction Research states this poses a significant downside risk for the equity prices of Indofood, its subsidiary Indofood Agri Resources (IndoAgri), and its parent company First Pacific.

- Undisclosed sources: 36% of crude palm oil processed in IndoAgri’s refineries was found to derive from undisclosed sources, creating both supply chain and reputational risks for its buyers and financiers.

Indofood and its associated companies in the Salim Group have also been criticized for weak corporate governance, which has been called “a risk multiplier” for deforestation risk. Climate Advisors and Indonesian policy group Auriga explain, “insider information and complex corporate structures can enable companies to cover up poor performance and relevant violations – making it difficult for investors and lenders to make informed financial decisions as risks are hidden, which decreases accountability.” Their research found that two of Indofood’s publicly traded palm oil subsidiaries – Salim Ivomas Pratama and London Sumatra – were “allegedly breaking Indonesia’s 1999 Anti-Monopoly Law.”

Indofood’s CEO Anthoni Salim has also been the subject of broader public concern over his involvement in private plantation businesses on the side that continue to clear rainforests and peatlands in Indonesia. In April this year, Salim was exposed for his indirect financial control and links via business associates to two palm oil plantation companies, PT Duta Rendra Mulya (PT DRM) and PT Sawit Khatulistiwa Lestari (PT SKL). These companies were found to have illegally cleared nearly 10,000 hectares of carbon-rich peatlands in the Ketungau peat forests of Borneo between 2013 – 2017, much of it categorized for protection by the Indonesian Government. These plantation assets are at risk of being stranded because of buyers’ “No Deforestation, No Peatland and No Exploitation” (NDPE) policies and Indonesian Government regulations to protect peatlands and forests.

Results from drone verification of deforested land on PT SKL (Nov 4 2017). Source: Aidenvironment, Palm oil sustainability assessment of Salim-related companies in Borneo peat forests, April 2018

Financial Sector Exposure and Its Response (or lack thereof)

The response by the financial sector has been confusing, muted, and disappointing, and it raises significant concerns about their commitment to sustainability, human rights, and even legality.

Top lenders, underwriters, and investors in the Salim Group. Source: forestsandfinance.org, Indofood Financial Statements & Bloomberg

As illustrated above, well-known banks and investors are financing the Salim Group with billions of dollars. Among the top lenders are Indonesian and Japanese banks, including Bank Central Asia, Mizuho Financial Group (Mizuho), and Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group (SMFG). While less exposed, more reputable banks such as Standard Chartered, Rabobank, and DBS also have outstanding loans to Indofood, while BNP Paribas is financing Indofood’s parent company First Pacific. The Salim Group’s complex corporate and ownership structures make it difficult for financiers to know how their money is actually being used.

One of the first to divest was the Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global, the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund. It withdrew its investments from IndoAgri and First Pacific because they “were considered to produce palm oil unsustainably.” Among banks, Deutsche Bank appears to have been the first to stop lending to Indofood and its subsidiaries following revelations of labor abuses. In April this year, Citigroup cancelled its loans to IndoAgri, while continuing its financing to other non-palm oil related businesses by Indofood. Notably, both Deutsche Bank and Citi have explicit prohibitions against forced labor and child labor.

Indofood’s egregious ESG risks should compel other financiers to act, especially those that have made explicit commitments that Indofood fails to meet. Mizuho recently strengthened its human rights due diligence policy, which is commendable; its response to Indofood will be a key test of the policy’s implementation. Standard Chartered, Rabobank, and DBS all have clear prohibitions against exploitation as well as development on peat. Meanwhile, BlackRock has called on all of its investee companies to make “a positive contribution to society” and to “benefit all of their stakeholders.” That should necessitate concerted engagement with and likely divestment from Indofood.

What’s necessary

Institutions providing financial services to Indofood and the wider Salim Group share a responsibility for the harmful environmental and human rights impacts resulting from its palm oil operations. This is in line with the OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Banks and investors need to issue an immediate ultimatum to Anthoni Salim that insists on the adoption of a genuine “No Deforestation, No Peatland and No Exploitation” policy that applies to the Salim Group and Anthoni Salim’s businesses-on-the-side; the establishment of a credible grievance mechanism; and independently verified corrective actions to remedy documented labor violations and existing land conflicts. In order to address ongoing risks, financiers need to demand a publicly available time-bound implementation plan that commits to the immediate cessation of all new plantation development, compliance with the requirements of the High Carbon Stock Approach, and investment in the restoration of the degraded peatlands.

Protecting and restoring the remaining rainforests and peatlands and respecting associated human rights are critical to meeting the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Climate Agreement. It’s time the financial system fully and publicly committed to being part of the solution.