Key Findings

- Widespread Illegal Palm Oil Production: 653 hectares (1,613 acres) of palm oil plantations have been established within the Rawa Singkil Wildlife reserve in violation of Indonesian law, with 453 hectares (1,117 acres) classified as productive. This suggests that illegal palm oil could already be entering the supply chains of major global brands and traders.

- Impacted Brands and Banks: Major brands implicated include Procter & Gamble, Nestlé, Mondelēz, PepsiCo, and Nissin Foods, alongside banks such as MUFG, Rabobank, and HSBC. These entities risk exposure to illegal palm oil produced and sourced from the reserve through their sourcing from or financing of traders caught sourcing illegal palm oil. Other banks exposed to further high-risk traders in the region include Singapore’s DBS, UOB, and OCBC; French Bank BNP Paribas; and Malaysian banks Maybank and CIMB.

- Increasing Deforestation Rates: Despite its status as a legally protected area in Indonesia, the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve saw a fourfold increase in deforestation between 2021 and 2023. An alarming 74% of total deforestation since 2016 occurred after the EUDR cut-off date of December 31, 2020, indicating a systematic disregard for legal protections and regulatory requirements. The unfolding crisis appears to be a systematic attempt to cause degradation in intact peat forest areas before the conclusion of the national government’s field validation of the reserve boundaries to officially reduce the reserve size and normalize the illegally cleared areas.

- New Loopholes: This investigation documents the rise of a new palm oil ‘laundering’ loophole in which wealthy land speculators use the cover of smallholder farmers to avoid accountability for illegal deforestation. The evidence presented demonstrates that palm oil remains the main driver of illegal deforestation inside the reserve, and the actors responsible are primarily land speculators, not family-managed smallholder farms.

High Resolution Deforestation

After a reported period of intense lobbying by industry groups, the European Commission proposed a year-long delay in implementing the European Union’s Deforestation Regulation (EUDR). Palm oil lobby groups argued that the EUDR due diligence and traceability requirements were burdensome and went “beyond what is reasonable to ensure sustainability.” They further argued that voluntary sustainable certifications like Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) present a “robust defense” against forest destruction.

While Indonesia’s national primary forest loss rates have fallen considerably since its peak in 2014, deforestation for oil palm spiked in 2023 and remains a leading driver of deforestation in some of Indonesia’s most biodiverse landscapes. This includes the nationally protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve, part of the wider Leuser Ecosystem known as the “Orangutan capital of the world”.

RAN investigations over the last decade have consistently shown how traders with RSPO-certified operations, including Apical (Royal Golden Eagle Group), Wilmar, Golden Agri Resources (Sinar Mas Group), Musim Mas, and Permata Hijau, are exposed to palm suppliers that are clearing peat forests and producing oil palm illegally inside the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. Their traceability, monitoring, and compliance systems remain demonstrably inadequate as they have been repeatedly exposed for sourcing palm oil produced illegally within the reserve.

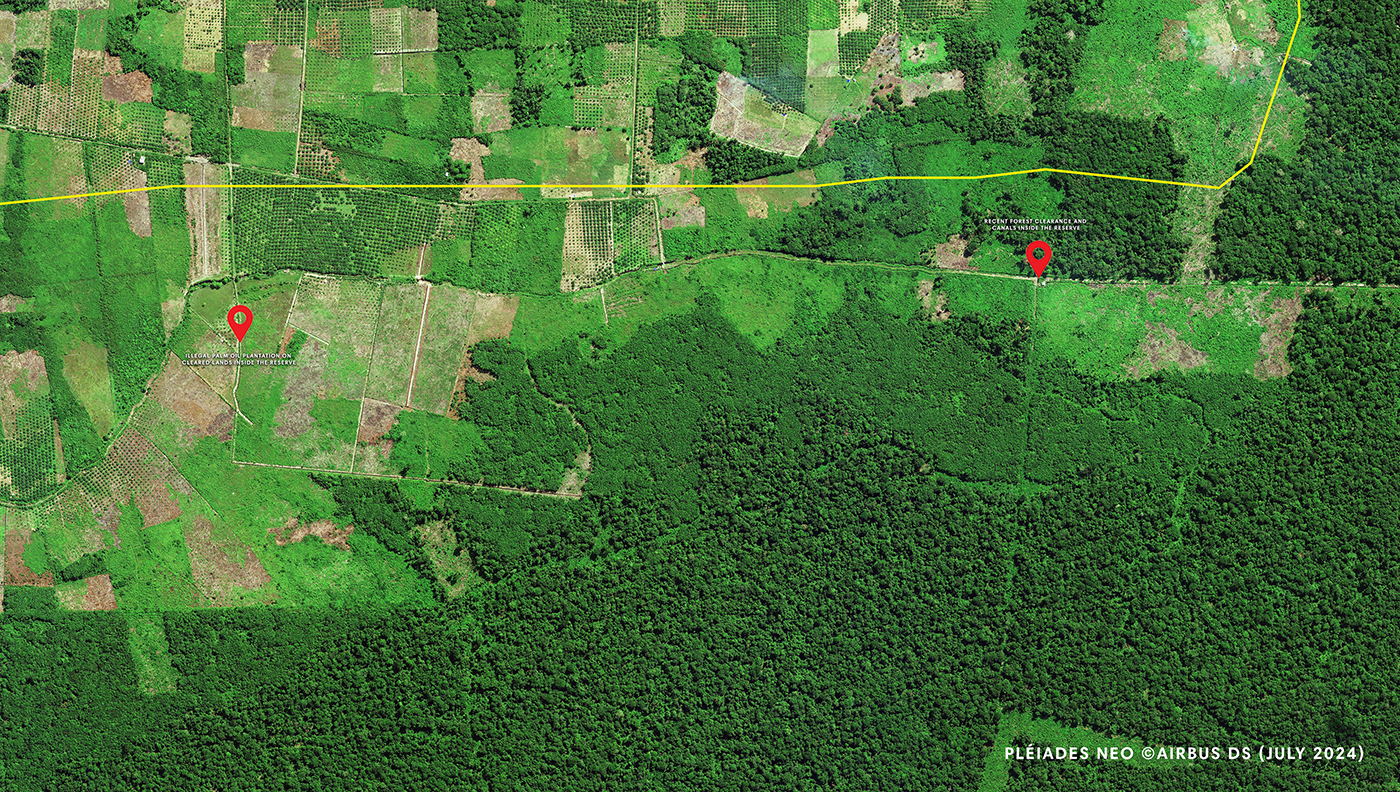

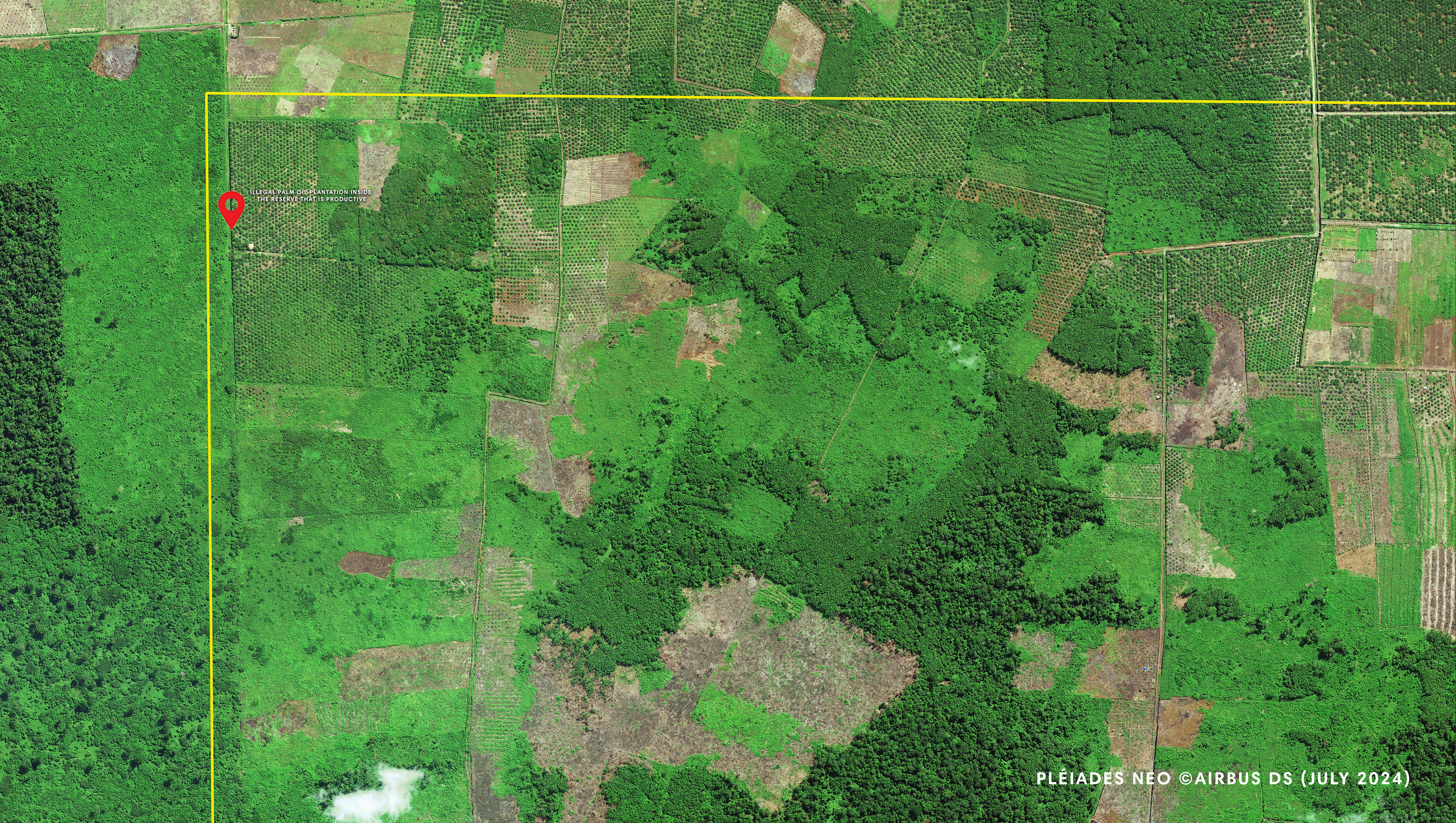

In July 2024, RAN commissioned satellites of Pléiades Neo to fly above the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve and capture high resolution images documenting the extent of illegal deforestation within the ‘orangutan capital of the world.’ These images provide unprecedented detail, allowing us to map the mosaic of illegal deforestation and oil palm production in the reserve and estimate the age of individual oil palms to determine when the clearance and planting occurred.

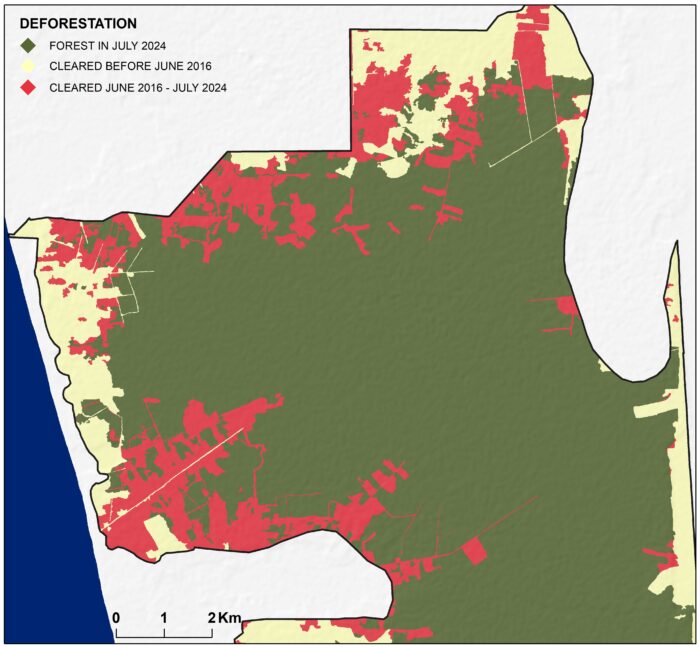

Alarmingly, deforestation was found to have increased inside the reserve after the adoption of ‘no-deforestation’ cut-off dates. The analysis, carried out by TreeMap, reveals 2,577 hectares (6,368 acres) of deforestation inside the nationally protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve since the December 2015 deforestation cut-off date adopted by the palm oil sector and major brands. Even more concerningly, it shows that the highest levels of deforestation, 74% of the total since 2016, occurred after the EUDR cut-off date of December 31, 2020. The scale of the destruction is shown in the high resolution imagery below:

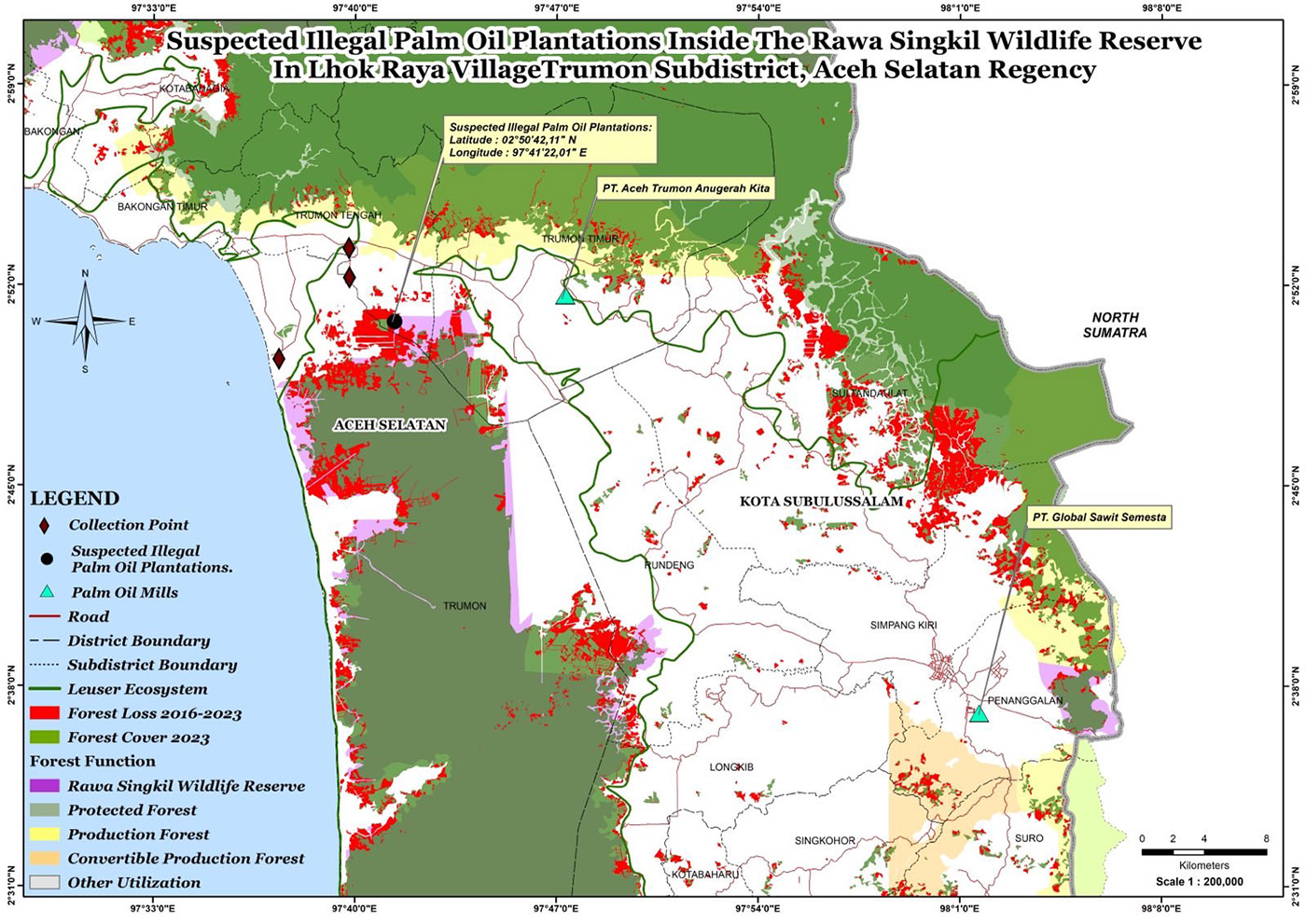

Imagery from Pléiades Neo, provided by Airbus, captured in July – September 2024, showing the extent of forest loss within the reserve in July 2024. Map provided by The TreeMap.

RAN has now published the imagery and results on Nusantara Atlas––a publicly available monitoring platform, powered by The TreeMap. This is the first time that high-resolution imagery of this level has been published, showing the extent of the palm oil-driven crisis in this protected wildlife reserve.

Given the imagery’s resolution, we could determine the extent of illegal palm oil planted within the reserve, how old the planted oil palms are, and when the lands they were grown on were cleared. A total of 653 hectares (1,613 acres) of illegal palm oil plantations were identified inside the protected reserve. Four hundred fifty-three hectares (1,117 acres) of these illegal palm oil plantations have a closed canopy and can be considered ‘productive,’ which takes three to four years after planting. Palm oil fruit that has been grown illegally in these locations could already be making its way into the supply chains of major brands.

A total of 200 hectares (494 acres) of oil palm plantings are less than 3 years old, meaning they were planted after the deforestation cut-off date of 2020 in the EUDR. These plantations will mature over the coming years, and once they produce fruit, they are also at risk of entering global supply chains–including the European Union–despite the fact that they were produced in a manner that is not compliant with the requirements of the EUDR regulation.

The maps below show the extent of illegal deforestation within the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve after December 2015––the deforestation cut-off dates adopted by major brands, the palm oil sector, and the European Union Deforestation Regulation.

Avoiding Traceability, Evading Accountability

The European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) requires traceability of raw materials to the geo-location of production. To comply with the EUDR–and to realize the implementation of No Deforestation, No Peatland, and No Exploitation Policies adopted by major brands and banks––actors in palm oil supply chains need to invest in effective traceability systems to the point of production and programs that support all suppliers to achieve compliance. For larger palm oil companies, this means traceability to government-allocated concessions. For smallholder farmers, this means the establishment of fully traceable supply chains that can trace oil palm fruit down to the farm level.

A functioning traceability system would, in this case, exclude palm fruit illegally produced in Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve from entering supply chains as palm oil grown in the reserve has been grown in violation of Indonesian laws and regulations, as well as deforestation cut-off dates in voluntary policies adopted by major brands, banks, and palm oil traders. RAN’s investigation found that the traceability, monitoring, and compliance systems of global brands and palm oil traders in their supply chains are insufficient and are failing to end the sourcing of Conflict Palm Oil produced within the protected reserve.

Instead of investing in effective traceability systems to the point of production and programs that support smallholders to achieve compliance, palm oil traders and industry lobby groups have argued that collecting geo-location data is too demanding due to logistical and financial obstacles, often citing its impact on smallholders. This is likely one line that influenced the decision by the EU Commission to propose a delay of EUDR implementation by a year, until December 31st, 2025, and to 2026 for smallholder suppliers. The industry-led Palm Oil Collaboration Group has developed a loophole called the ‘minimal smallholder deforestation’ approach (this concept is explained in more detail in RAN’s report). In places like the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve, this innocuous-seeming loophole can result in a “death by a thousand cuts”. It enables the lack of full traceability to the source to continue in global palm oil supply chains and for “deforestation-free” claims to be made in a way that disregards deforestation driven by a different class of actors: land speculators.

Under the Magnifying Glass: The Land Speculators Behind Illegal Deforestation and Palm Oil Development in the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve

RAN’s field investigations confirmed that the actors responsible for the recent uptick in deforestation in the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve were land speculators, not family smallholder farmers. Land speculators are locally influential individuals who often have formal positions that enable them to sell/trade land titles with outside parties. They will typically have multiple land ownership certificates with total holdings much more significant than family smallholder farmers. They often manage oil palm collection and dealing businesses and have access to financial resources that enable the deployment of expensive heavy machinery like excavators for land clearing and canal digging.

In September-October 2024, we documented the illegal operations of land speculators where they could be identified with satellite imagery. The location of these illegal plantations within the protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve (outlined in yellow) is shown in the map below. High-quality imagery of each illegal plantation area is shown below, and a complete profile of each of these land speculators is provided in the report. RAN has decided not to publish the names of the new land speculators identified.

MAP 1- LOCATION OF LAND SPECULATORS’ ILLEGAL PALM OIL OPERATIONS IN RAWA SINGKIL WILDLIFE RESERVE

RAN’s research confirmed the ongoing drainage and clearing of peat forest areas for illegal oil palm plantations inside the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. It also indicates that some of the actors responsible supply their illegally produced palm oil to two crude palm oil mills in the region that supply major traders, including Apical (Royal Golden Eagle Group), Musim Mas, and Permata Hijau. These traders supply major brands like Procter & Gamble, Nestlé, Mondelēz, PepsiCo, and Nissin Foods. They are funded by banks with NDPE policies for palm oil financing, including Japanese bank MUFG (for a full breakdown of financiers, see below).

Land Speculator Case 1: Active Deforestation, Illegal Palm Oil Plantations in Seuneubok Jaya, Aceh Selatan, and Palm Oil Collection Points that are Accepting Illegally Produced Palm Oil

This land speculator controls 120 hectares (296 acres) of land in three areas inside the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. This image shows active logging, forest clearance, and the creation of peatland drainage canals inside the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve in September 2024. Other areas within the protected reserve were cleared in June 2022, and field investigations undertaken in February 2024 confirmed that these areas now have young oil palm plantings. Zoom into the highlighted areas to see more.

GPS Coordinates for recent forest clearance and canals inside the reserve: 02°43’39.42 N 97°41’27.40 E

This land speculator owns a palm oil brokering business called UD Daya, which has a collection point in Ie Meudama. Field investigations undertaken in September and October 2024 documented this land speculator accepting oil palm fruit grown in illegal palm oil plantations inside the reserve. Investigators followed trucks from his collection points to a nearby mill, showing that this land speculator supplies illegally produced palm oil fruits to a mill called PT. Global Sawit Semesta, which supplies traders and global brands.

You can also view high resolution imagery that shows the extent of forest loss between 2016 and 2024 for Case 1 on Nusantara Atlas.

Land Speculator Case 2: Deforestation, Use of Fire, and Illegal Palm Oil Plantations in Ie Meudama Village, Aceh Selatan.

This land speculator controls 10ha (25 acres) inside Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. The most recent documentation of illegal deforestation, fire use, and oil palm plantings within the reserve was undertaken in February 2024. Earlier clearing was identified using satellite analysis in June 2022. Zoom into the highlighted areas to see more.

You can also view high resolution imagery that shows the extent of forest loss between 2016 and 2024 for Case 2 on Nusantara Atlas.

Land Speculator Case 3: New Canal Development, Deforestation, and Illegal Palm Oil Plantations in Ie Meudama Village, Aceh Selatan

This land speculator controls 50 ha (124 acres) inside Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. The most recent illegal forest clearance and canal development documentation was undertaken in February 2024. Zoom into the highlighted areas to see more.

You can also view high resolution imagery that shows the extent of forest loss between 2016 and 2024 for Case 3 on Nusantara Atlas.

Land Speculator Case 4: Illegal Deforestation in Seuneubok Jaya, Aceh Selatan

This land speculator controls 100 hectares (247 acres). The most recent illegal forest clearance and canal construction documentation was undertaken in February 2024. Earlier clearing was observed via satellite analysis in October 2023. Zoom into the highlighted areas to see more.

You can also view high resolution imagery that shows the extent of forest loss between 2016 and 2024 for Case 4 on Nusantara Atlas.

Land Speculator 5: Illegally Produced Palm Oil Supplies Palm Oil Traders and Global Brands, Lhok Raya, Aceh Selatan.

This land speculator controls 18 hectares (44 acres) within the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. Seven hectares (17 acres) are productive oil palm plantations, which were cleared in 2012. Oil palm plantings began in 2014 and continued until 2017. Zoom into the highlighted areas to see more.

You can also view high resolution imagery that shows the extent of forest loss between 2016 and 2024 for Case 5 on Nusantara Atlas.

Evidence obtained by RAN indicates that this land speculator has lands illegally developed into oil palm plantations inside the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve. RAN’s investigations found that some of the plantations produce palm oil fruit that is being harvested and sold to a dealer with a nearby collection point. The dealer is supplying palm oil fruits to PT. Global Sawit Semesta (PT. GSS)––a mill supplying Royal Golden Eagle (Apical), Musim Mas, and Permata Hijau Group––and PT. Aceh Trumon Anugerah Kita (PT. ATAK), which supplies Permata Hijau Group and Pacific Palmindo Industries. These traders supply global brands with illegally produced palm oil produced by this land speculator, including Procter & Gamble, Nestlé, Mondelēz, PepsiCo, and Nissin Foods. Review the report and the images and evidence shown below for details on the full investigation.

EVIDENCE SHOWING LAND SPECULATOR 5 SELLING ILLEGALLY PRODUCED PALM OIL TO TWO PALM OIL MILLS––PT. GSS and PT. ATAK

Global Brands and Banks Driving the Palm Oil Crisis

Previous exposés published by RAN show that illegally produced palm oil has been used to manufacture snack foods sold worldwide by Procter & Gamble, Nestlé, Mondelēz, Colgate-Palmolive, PepsiCo, Unilever, Kao, and Nissin Foods. In 2019 and again in 2022, these brands purchased palm oil from multiple mills that have continued to source palm oil, resulting from illegally clearing lowland rainforests within the nationally protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

RAN’s field investigations in September – October 2024 again found evidence that palm oil grown illegally inside the protected Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve is being supplied to a mill repeatedly exposed for sourcing and supplying illegal palm oil. The mill, called PT. Global Sawit Semesta, continues to be listed as a supplier to Procter & Gamble, Nestlé, Mondelēz, PepsiCo, and Nissin Foods. This means these brands are at risk of manufacturing their consumer products using illegal palm oil produced at the expense of the Orangutan Capital of the World.

Similarly, banks with ‘No Deforestation, No Peatland, No Exploitation’ policies for the palm oil sector continue to finance traders exposed to palm oil illegally produced inside the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve despite their evident lack of adequate traceability, monitoring, and compliance systems. The figure below shows the credit flows from banks with NDPE policies to the five traders sourcing palm oil from within the nationally protected reserve and the wider Leuser Ecosystem. Banks financing traders demonstrably exposed to illegal palm oil in 2024 include MUFG, Rabobank, UBS, HSBC, and ING. A significant proportion of the credit flowing to these palm oil traders has been arranged as sustainability-linked loans, with MUFG contributing $630 million to Royal Golden Eagle Group and Rabobank contributing $217 million to Musim Mas Group (due to lags in reporting, Rabobank’s most recent deal is not yet captured in Figure 1 below). Under these sustainability loans, the amount repaid by these traders depends on their performance against targets including no deforestation supply chains and progress on transparency and traceability. The evidence presented above calls into question whether these groups meet agreed targets. Other banks exposed to other high-risk traders in the region include Singapore’s DBS, UOB, and OCBC, BNP Paribas, and Malaysian banks Maybank and CIMB.

A Solution for Singkil

The global market now demands palm oil free of deforestation, peatland development, and exploitation of communities and workers, especially in global biodiversity hotspots like the Leuser Ecosystem. However, these commitments still need to be adequately implemented on the frontlines of palm oil expansion in the Orangutan Capital of the World in Aceh, Indonesia, where deforestation is increasing. Advancements are needed in the palm oil industry because global brands and their customers remain exposed to illegal sources of Conflict Palm Oil grown by land speculators inside the Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve.

Investments are needed to establish multi-stakeholder programs that develop and implement a shared and just vision to protect the lowland rainforests and peatlands of the Singkil-Bengkung region from further destruction. These programs should also diversify economies and drive investments in low-carbon, community-led, small-scale agriculture that respects the rights of communities and smallholder farmers to manage their lands and improve livelihoods. RAN calls on all brands, traders, and banks complicit in the Singkil crisis to invest in these programs without delay.

The companies named in this report were asked to comment on the findings presented. Details of their responses are available at https://www.ran.org/leuser-watch/orangutan-capital-under-siege/.