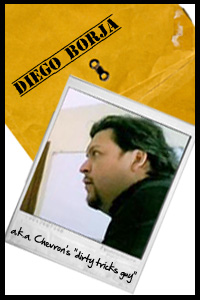

The saga of Chevron’s self-described “dirty tricks guy” continues.

As a refresher: Diego Borja is the guy who claimed in 2009 that he had video showing the Ecuadorean judge presiding over the lawsuit against Chevron accepting a bribe. Chevron breathlessly announced the bribery “scandal” and claimed Borja was just a concerned citizen with no connection to the company.

As it turned out, Borja was a Chevron contractor. And the video didn’t actually show any bribe taking place – because there had not actually been any bribe. Borja’s attempt to entrap the judge failed. Though he’d done nothing wrong, the Ecuadorean judge did recuse himself in order to ensure the trial was not tainted by the false allegations against him. His recusal caused at least a two-year delay in the trial.

For these shameful actions, we named Borja one of Chevron’s “Human Rights Hitmen.”

Borja’s lawyer, San Francisco-based Ted Cassman, has now made the rather unusual admission that his client could face potential criminal liability for his role in the failed sting operation.

The Amazon Defense Coalition has the scoop:

Borja, who Chevron moved to the United States just before the scandal became public in August 2009, is already under investigation by criminal prosecutors in Ecuador. He lives in an undisclosed location in Houston, where Chevron pays him a salary to maintain his loyalty while he does no work, said [Karen] Hinton, [U.S. spokesperson for the Ecuadorians who are fighting Chevron to clean-up their ancestral lands].

Casselman made the comments about Borja’s potential criminal liability in the U.S. on September 28th in San Francisco during a discovery hearing where Chevron’s lawyers are fighting feverishly to prevent the release of documents related to the entrapment scheme. The Ecuadorian plaintiffs believe Borja’s actions on behalf of Chevron could violate the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which prohibits American businesses from bribing foreign officials, said Hinton.

The plaintiffs also believe Chevron helped Borja secure political asylum in the United States under false pretenses so he would be out of reach of Ecuadorian investigative authorities, Hinton added.

The plaintiffs assert that the documents sought from Borja and the Mason Investigative Group will shed light on what they call Chevron’s Nixon-style “dirty tricks” campaign to undermine the Ecuador trial. In phone conversations taped by a friend after the sting became public, Borja confessed that he had set up dummy corporations for Chevron, doctored scientific sampling results that were submitted to the court, and had information that would allow the plaintiffs to win the litigation immediately. He also bragged to his friend on the tapes that “crime does pay.”