For Indonesian translation click here.

For Japanese translation click here.

On a Friday afternoon in late February 2015, a young farmer named Indra Pelani was riding on the back of a friend’s motorbike through the countryside of Jambi Province, on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia. Pelani and his friend were headed to a rice harvest festival, looking forward to a day of celebration. But they never made it.

The two friends had grown up in neighboring communities — villages that had lived, worked, and farmed in the area for countless generations but, over time, had watched as their communities’ land and forest were given away to pulp and paper companies. These massive Agribusiness companies cleared native forests and put heavily guarded pulp and paper plantations in their place — destroying the communities’ farms and traditional sources of livelihood and dominating and militarizing the area in the process.

On that particular Friday afternoon, Indra Pelani and his friend tried to pass through a guarded checkpoint on a road which cut through an acacia plantation owned by Asia Pulp and Paper — one of the world’s largest paper companies which is owned by an even larger conglomerate called Sinar Mas Group. A prominent farmers’ union member and environmental activist who was organizing to reclaim his community’s land, twenty-two-year-old Pelani was recognized by the guards at the checkpoint. The guards grabbed Pelani off his friend’s motorbike, who sped away to find help. Tragically, help did not come in time. Pelani was found a day later, his body dumped in a swamp, severely beaten, stabbed, and bound at the hands and feet.

Indra Pelani’s brutal murder caused international uproar and activism that continues today, but it is sadly only one entry on a long, terrible list of injustices that communities on the frontlines of plantation agriculture face. The companies committing these human rights abuses and driving massive deforestation in Indonesia are propped up by business contracts with global brands and banks, and the money just keeps on flowing.

Sinar Mas Group — A Network Of Human Rights Abuses

Sinar Mas Group (SMG) owns Asia Pulp and Paper among many other companies. According to multiple reports, from local and international media and civil rights organizations, it has one of the worst records on human rights abuses and environmental destruction, including land grabbing, intimidation, criminalization, and violence.1 SMG refuses to follow international human rights norms, fails to ensure that communities are given the right to give or withhold consent to development on their lands and, even when agreements have been made between SMG and communities, SMG has failed to uphold those agreements. SMG continues to inadequately handle community grievances and refuses to provide remedy to the hundreds of communities it has impacted.

And yet, SMG continues to supply major brands with palm oil and pulp and paper, and international banks continue to lend SMG more and more money. Global brands like Mars, Mondelēz, Procter & Gamble, Nestlé, Unilever, Colgate-Palmolive, PepsiCo, and Kao, all use SMG-owned palm oil to produce the snacks, instant noodles, and other household goods that line our store shelves. Japanese brand Nissin may also be implicated as they buy from Fuji Oils, which in turn purchases from the SMG group. Nestlé also buys its pulp and paper through SMG-owned Asia Pulp and Paper, along with likely many other companies that fail to disclose their paper suppliers. SMG is also the largest recipient of bank financing to the forest-risk sector in Southeast Asia, with a credit value of USD 20 billion during the last five years (2015-20Q1). Some of the biggest lenders include Indonesian banks Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) and Bank Negara Indonesia (BNI), Japanese banks Mizuho Financial Group and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG), Malaysia’s CIMB and China’s ICBC.

Many of these same brands and banks have public policies and commitments to uphold human rights but ignore SMG’s wide-spread human rights violations. These brands and banks like to boast about their latest positive “initiatives” while they support SMG’s refusal to respect Indigenous and community rights. This must stop. Banks and brands must immediately stop all new business deals with Sinar Mas Group (SMG) until it can prove that it has remedied the social and environmental harm it and its suppliers have caused. SMG must prove that it is truly implementing its supposed commitments to ‘No Deforestation, No Expansion on Peatlands, and No Exploitation of Communities and Workers’ and has met the demands of affected communities.

According to Environmental Paper Network’s 2019 report, in just five provinces in Indonesia, at least 107 villages or communities are in active conflict with APP affiliates or its suppliers and 544 villages were identified as sites of potential conflict, covering an area of more than 2.5 million hectares. The following are just some of the community conflict cases that Sinar Mas Group has failed to address. The stories of these communities are key examples of how Sinar Mas Group has violated human rights:

Violence and Intimidation Against the Sekato Jaya farmer’s group in the community of Lubuk Mandarsah Village in Jambi, Indonesia

Lubuk Mandarsah Village, located in Jambi province on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia, is home to over 6,000 households. The community is predominantly Jambi Malays and Indigenous Anak Dalam tribes who have lived in the area for generations. The majority of the community live and work as rice and vegetable farmers and are very dependent on the land. Access to their community-owned land is increasingly limited, however, because much of the land has been designated as a part of the nearby Bukit Tiga Puluh National Park or given to the industrial plantation concession company PT. Wira Karya Sakti (PT. WKS), which is owned by Asia Pulp & Paper (APP).

The conflicts between PT. WKS and the community started in 2007 in one of the village’s hamlets, Pelayang Tebat. After building an access road to its concession in the area, the company began to clear land on both sides of the road, including land that was being used as farmland by the community.2 Based on mapping done by the community, Tebo Farmer Union, and environmental group WALHI Jambi in 2013, the total area of community-managed lands that had been taken over by the company was 1,500 hectares — or over 2,800 football fields.3 The conflict escalated into a clash between the company and the community on December 28, 2007, when community members allegedly burned PT. WKS’s heavy-duty machines, which were clearing the community’s agricultural land.4 The incident led to 9 farmers being arrested and jailed for 15 months.

Local environmental group WALHI JAMBI alleges that, over the years, PT. WKS has only continued to intimidate and attack the communities, giving the following examples:

- On March 6, 2013, a farmer named Kariono Setio was arrested by the district police, after PT. WKS accused Setio of clearing a piece of land in the company’s ‘conservation’ area, which had been established on traditionally-owned farm land without the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) of the community. Kariono was forced to stop working on his farm land in order to avoid conviction.5

- On February 27, 2015, Indra Pelani was beaten, kidnapped, and murdered by the PT. WKS security team.6

- On March 4, 2020, PT. WKS used drones to spread toxic herbicides to destroy vegetables, chillies, jengkol (a tree with edible seeds used for food and medicine) and oil palm trees that had just been planted by the community. The Indonesian government had begun implementing large-scale social restriction policies in order to cope with the coronavirus outbreak, and so it was easier for PT. WKS to spread the herbicides without oversight. Halim, one of the community members, reported that approximately two hectares of community gardens were destroyed and the community’s harvests failed as a result of the herbicide spreading.

- PT. WKS continues to intimidate the community. Also in March 2020, a community member was reported to the police by PT. WKS for clearing disputed land believed to be part of the communities’ Indigenous land.7 On April 28, 2020, soldiers deliberately fired two shots into the air when Mr. Agus, a community member, was maintaining one of the community’s gardens.

Since the conflicts started, the community has been organized in resistance and has attempted to address the issues with the company in a number of ways, including staging demonstrations in front of government and company offices, blocking the company’s field activities, and attempting to negotiate with the company.

Regarding the most recent incidents, APP/SMG stated the “issue has been resolved through mediation” and claimed that a community representative acknowledged a smaller area of the communities’ crops had actually been destroyed by the drones. The local NGOs contend that no meaningful mediation took place and the longstanding conflict between the Lubuk Mandarsah community and PT. WKS remains.

Criminalization of Indigenous Sakai Tribe in Riau, Indonesia

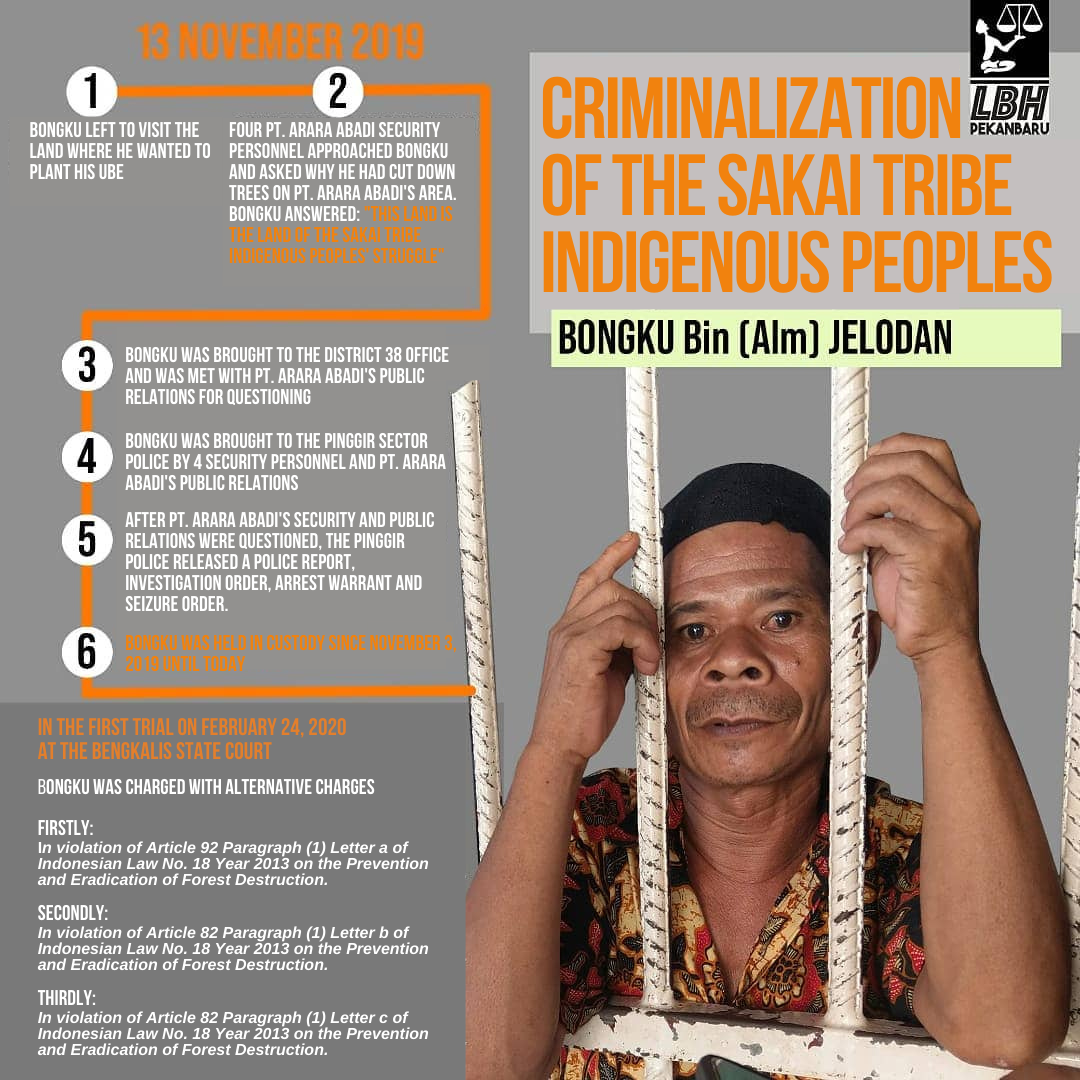

The Sinar Mas Group’s record of human rights violations is not limited to Lubuk Mandarsah Village. According to local news sources, SMG has also violated the community rights of the Indigenous Sakai tribe in Bengkalis, Riau province. In this community, a local farmer was criminalized for cutting down trees on community-owned land which was claimed by APP/Sinar Mas-owned company PT. Arara Abadi (PT. AA).

This conflict started in 2001, when PT. AA cleared 327 ha of land, claimed to be community-owned and traditionally-owned by the Indigenous communities of Sakai Batin Beringin and Penaso, destroying much needed food sources.

Fifty-eight-year-old Bongku Bin Jelodan, a member of the Sakai Batin Beringin community, is one of the community members criminalized by the conflict. Bongku is a farmer who cultivates cassava and a local sweet potato called Ubi Menggalo (Manihot glaziovii), which can be processed into Menggalo Mersik – one of the traditional foods of the Sakai. Like many Indigenous peoples in Indonesia, the Sakai are nomadic farmers that depend on the forest and its natural products.

The criminalization started when Bongku cultivated new land to grow sweet potatoes. Bongku cleared an area of 200 m2, cutting down about 20 acacia trees in November 2019.8 The cleared land is part of the Indigenous Sakai tribe’s communal lands, although it is currently legally designated as part of the industrial plantation forest concessions of APP/Sinar Mas-owned PT. AA.

Bongku’s first trial was in February 2020, and on May 18, 2020, the Panel of Judges sentenced Bongku to one year in prison and a fine of Rp. 200 million (over $14,000 USD) for cutting acacia trees inside PT. AA’s concession. The Panel of Judges found Bongku guilty of violating the 2013 Law on Prevention and Eradication of Forest Destruction, a law meant to outlaw organized forest destruction but is often used to criminalize communities.9

Since 2015, the Sakai communities have sought recognition of their customary land rights, including the land managed by Bongku, from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry but no recognition has been issued.10 In its statement, APP claimed “the Ministry of Environment and Forestry is facilitating the conflict resolution moving forward” and that “PT. AA remains committed to follow the process”.

Bongku was released after being imprisoned for seven months due to COVID-19 concerns. Local civil society groups warn the case leaves the land dispute open-ended and cases of criminalization like Bongku will likely continue until the land conflict is resolved and the Sakai’s Indigenous land is recognized.

Violating Labor and Human Rights on Palm Oil Plantations in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia

SMG’s track record of human rights violations is well documented and has been committed not only by its pulp and paper division but also by its palm oil operation. Civil society and labor unions have similarly documented human rights and labor abuses committed by Golden Agri Resources (GAR), another subsidiary of SMG.

In a 2018 report, Sawit Watch and Asia Monitor Resource Center interviewed 49 palm oil plantation workers about the abuses they experienced in working on GAR’s two palm oil plantations in Central Kalimantan: PT. Tapian Nadenggan and PT. Mitra Karya Agroindo.

The violations included unfair work systems, occupational health and safety issues, low wages, poor living conditions, gender discrimination, and hiding workers so that the audit team of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) — the leading certifier of ‘sustainable’ palm oil — couldn’t interview them. Trade unions and civil society groups have also repeatedly raised concerns about violations of labor rights, including unregulated work contracts, unpaid overtime, unwarranted dismissals, and suppression of trade unions on palm oil plantations owned by PT. Sawit Mas Sejahtera in South Sumatra, which is also owned by GAR.

Forest Peoples Programme (FPP) and Elk Hills Research have also filed a complaint to the RSPO recently about alleged violations of licensing regulations and indications of corruption in eight GAR concessions in Central Kalimantan, including the discovery of violations of labor rights in the two concessions mentioned above. FPP and local NGOs previously filed a number of complaints against GAR for violations of the right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) in community land release processes, including in Liberia.

Sourcing Palm Oil from the Lands of Pante Cermin Village, Aceh, Sumatra, Indonesia

In September 2020, RAN uncovered evidence that Sinar Mas Group’s palm oil arm, Golden Agri Resources (GAR), was sourcing palm oil from a mill that was supplied by PT. Dua Perkasa Lestari (DPL) — a palm oil plantation company that has been managing a plantation on the customary lands of the Pante Cermin Village, in Aceh Barat Daya District, Aceh Province, on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia.

The conflict between the community of Pante Cermin Village and PT. DPL began in 2006. Displaced by the conflict between Aceh’s separatist movement (GAM) and the Indonesian army, the community had returned to their village to find PT. DPL operating on their land. Although the community had legal documentation of land ownership (a Statement of Physical Ownership of Land, or SPORADIK), PT. DPL continued to clear the community’s established food crops to develop an oil palm plantation. Over the years, intimidation has escalated. In 2014, the company has used the military Mobile Brigade (Brimob) to destroy the community’s houses and crops, surveil the community, and has even fired warning shots at the community, nearly hitting a community member in the head.11

A legal analysis by the Banda Aceh Legal Aid Institute has found that PT. DPL had irregularities in its palm oil plantation permit. The permit issuance did not involve local communities despite it being located on farms managed by local communities since 1992. There were discrepancies between the location permit, plantation business permit and the business use rights (Hak Guna Usaha) regarding the location of the plantation. The plantation was also developed on peatlands with a depth beyond 3 meters.

Since the relationship between GAR and PT. DPL became public, GAR announced that it would stop sourcing from PT. DPL. However, GAR has failed to engage with PT. DPL directly to ensure remedy is secured for the Pante Cermin community. This decades-long land conflict shows weaknesses in GAR/Sinar Mas Group’s ability to implement its human rights policies, establish effective human rights due diligence systems, and detect and resolve non-compliance in its supply chain.

The Need For Free, Prior and Informed Consent

The cases above make it clear that SMG’s human rights violations do not only occur in one sector or a handful of plantations, but across commodities, regions and throughout its supply chain including third-party suppliers. The agribusiness arms of SMG’s subsidiaries, APP and GAR, have failed to fulfill their own commitments, including those to respect human rights, the rights of local communities and the Free, Prior and Informed Consent process.

What Global Brands and Banks Must Do

The affected communities demand that Sinar Mas Group:

- Immediately resolve all land conflicts associated with Sinar Mas Group’s operations, including conflicts with the communities in Lubuk Mandarsah in Jambi, Sakai Indigenous Communities in Riau, and communities in Pante Cermin village in Aceh.

- End all forms of intimidation and criminalization against impacted communities and environmental and rights defenders.

- Respect and support the recognition of Indigenous land rights by returning land within company concessions to the communities.

- Ensure fair and decent working and living conditions for workers on SMG’s plantations.

Support These Communities

Sign this petition to continue to shed light on the criminalization of Indigenous rights defenders like Pak Bongku: #FreeBongku End Criminalization of Indigenous Peoples!

- See for example: https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/indonesia-study-reveals-asia-pulp-papersinar-mas-involvement-in-hundreds-of-community-conflicts/; and https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/09/26/singapore-moves-against-indonesian-firms-over-haze.html

- Konsorsium Pembaruan Agraria. Suara Pembaruan Agraria Edisi 9: Agenda Reforma Agraria Pemimpin Baru. 2014. Pages 72-74.

- Mongabay Indonesia, Konflik lahan masyarakat Tebo dengan PT. WKS terus berlarut, 8 Juni 2020, Jakarta-Indonesia.

- WALHI. 2018. Briefing Paper Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia: Selembar Kertas dan Jejak Kejahatan Korporasi. 12 Februari. Jakarta, Indonesia.

- Walhi Jambi, Assessment report (Unpublished), Januari 2016.

- WALHI Jambi, Investigation Findings, Reka Ulang Kasus Pembunuhan Indra Pelani, Tersangka Pembunuhan, March 2015.

- Walhi Jambi. Siaran Pers: Kronologis Kekejaman dan Intimidasi PT WKS Terhadap Masyarakat (KT Sekato Jaya) Desa Lumbuk Mandarsah, Tebo – Jambi. June 2020.

- Tempo Magazine. Kekeliruan Hakim yang Menghukum Bongku Karena Menebang Pohon. May 2020 Edition.

- LBH Pekanbaru. Pak Bongku Bukan Pelaku Perusakan Hutan, Berikan Keadilan Untuk Masyarakat Adat. April 2020.

- Mongabay. Mau Tanam Ubi di Lahan Sengketa dengan Perusahaan, Orang Sakai Terjerat Hukum Merusak Hutan. May 2020.

- YLBHI-LBH Banda Aceh. Legal Opinion (Pendapat Hukum): Sengketa Lahan Antara Masyarakat Desa Pante Cermin Kecamatan Babah Rot Kabupaten Aceh Barat Daya Dengan PT. Dua Perkasa Lestari. 2019.